Category: Product Marketing

-

Everything So Far

All of my PowerPoints so far. Most of what I know about marketing up to this point!

-

How We Grew Marketing Sourced Pipeline by 20% in One Quarter

We’re about to go into our quarterly review period at Redgate. We don’t just run QBRs, we also run reviews across all parts of the business. These are a chance to examine the last three months – what worked? What’s going well? What’s not going well and needs fixing? All part of a strong agile…

-

Join a Scaleup to Scale Your Career

It’s hard getting ahead in Marketing. It’s a discipline changing every year (certainly true of 2020), it covers an enormous breadth of disciplines which need a great variety of skills and it’s notoriously difficult to prove the impact of your work. So what can you do to give yourself the best chance of success? Of…

-

Brand Amplifiers

I’m writing this on my way to the Sirius Decision Summit in Vegas (sitting in Terminal 3). I’m hoping to get a lot out of the conference (though I’m currently in option paralysis mode – too many sessions to choose from). But this post is about a very small part of that conference – though…

-

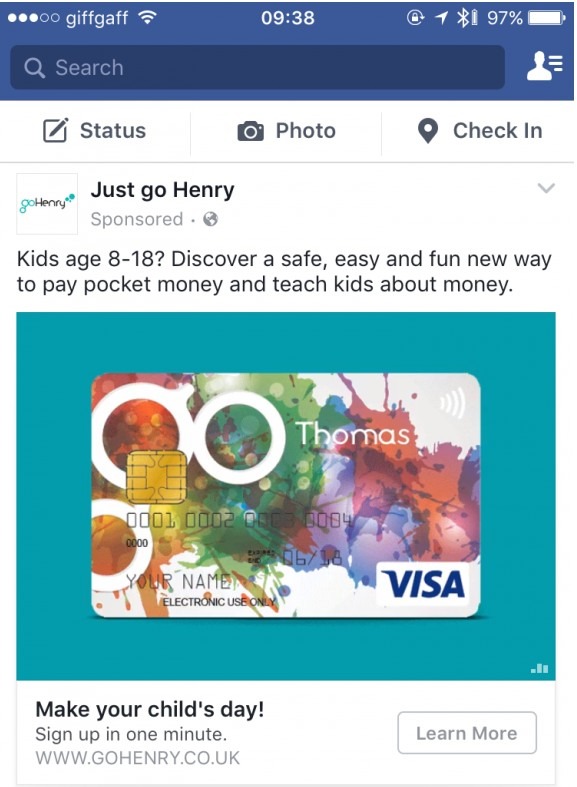

Anatomy of a Great Ad

It’s easy to forget, amongst the talk of marketing automation, social media strategy, customer experience, lead nurturing and so on, that you still need well written, well targeted and well designed ads to reach new customers. I spotted a great example this week, and just wanted to run through what I thought was great about…

-

Getting Stuff Done as a Product Marketing Manager

I hardly know a Product Marketing Manager who isn’t overwhelmed by his or her workload. As I’ve written previously, this is at least in part because of the vast number of activities that PMMs “should” be doing – how can you not being doing your job properly if you don’t, at least, have a full…

-

My 10 Biggest Marketing Screw-ups of 2013

It’s nearing Christmas, time for “Top 10…” and “Round up of 2013″ style posts, so here’s mine. One of my failings is that I’m a terrible self-critic, so I thought I’d write a piece on “My 10 biggest marketing screw-ups this year”. I don’t think I’ll get fired because luckily I work at a place…

-

Market Sizing – Old vs. New Markets

I was attempting some market sizing activity this week. It’s something I haven’t done for a few months and quite frankly I’d forgotten how hard it was. I start from a premise that the future is completely unpredictable. Really, aren’t we kidding ourselves when we think we can predict how many people will buy our…

-

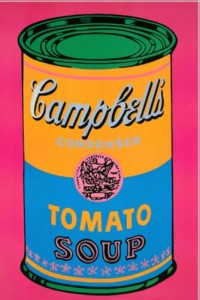

My Product is Great. Why Do I Need a Marketing Department?

Well, I still hear this question and there is some logic behind it. I’ve created a product of beauty and wonder, why do I need to invoke the dark arts of marketing to get it out there? Won’t its greatness shine through and act as a beacon to all those lovely customers with their dollars…

-

Waiting for Google

This isn’t going to be a very exciting post unfortunately, though it was supposed to be. I visited the UK Google offices this week to have a chat about the future of Google Analytics, well Google Universal really. I was hoping for some help, some tricks and tips, perhaps a few sneak peeks at a roadmap…

-

What I Should Be Doing as a Marketer. But Won’t Be

“Should” is a complicated – and dangerous – word in marketing. How many times have you read blogs and articles proclaiming that you “Should be doing more mobile marketing”, that you “Should have full content strategy”, that you “Should be creating personae for all of you target segments”, “Should be doing more on Twitter”? And…

-

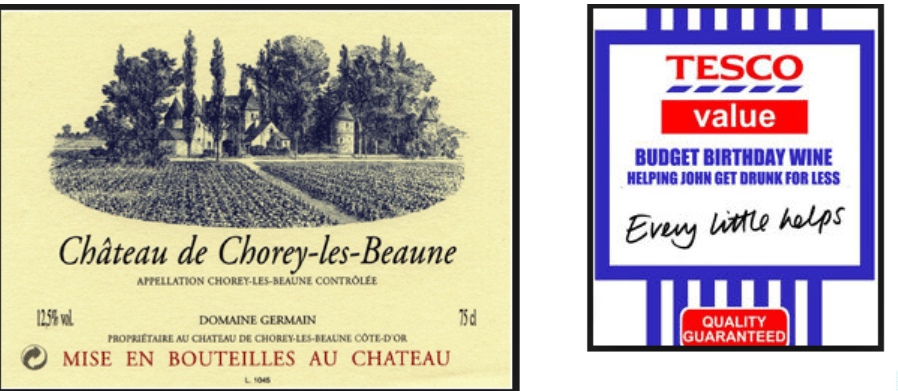

Value and Predictable Revenue Improvements

I really like this very simple post about how to buy wine, when you don’t really know much about it (which is definitely me). Basically, select a price (say, £7.95), then select a wine at that price. That’s kind of it. And what Evan Davis is saying is “Statistically, give or take anomalies, most wines…

-

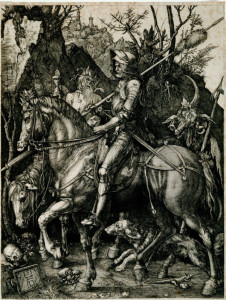

Competition, Disruptive Innovation and Total Recall

A key part of any product marketing role is analysing the competition for your product. Put simply, when your potential customers are looking to solve a particular problem or take advantage of an opportunity, what are the options that they see, one of which (hopefully!) is you? Sometimes this job is easy when you have…

-

Why Product Managers Often Aren’t Great at Marketing

Back when I was a developer, many years ago, I worked with a superb sales person – an ex-McKinsey sales person – who had been tasked with explaining to all us techies “What Sales Did”. Of course we already knew the answer – “Nothing, except get paid more than us, drive nicer cars, get more…

-

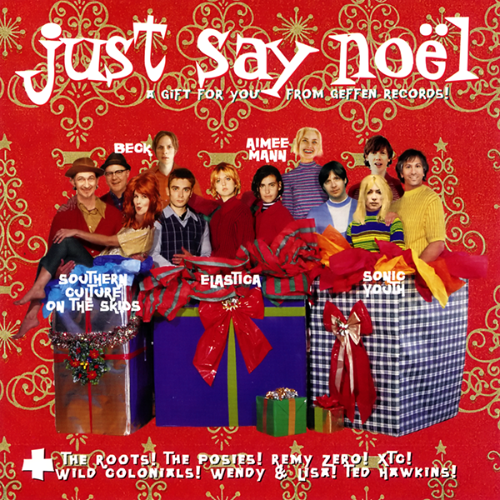

Favourite marketing posts of 2012

This post is now 11 years old so a lot of the links no longer work! This is my last post of 2012 before breaking up for Christmas and I thought I’d finish with one of those lazy “Everyone’s out for Christmas, let’s just re-use some old material” posts, summarising my favourite articles that I’ve…

-

Lean Personas – How to Make Personas More Useful

First of all, I prefer the term “Personas” to “Personae”. Doesn’t “Personae” just seem pretentious, n’est-ce que pas? Anyway, the point is, I’ve always struggled, over the years, to find personas a useful tool in marketing. I’m specifically talking about marketing here, rather than user-centred design – I know these are two sides of the same coin,…

-

Product Marketing and Product Management Roles

I wrote a brief post, about the different roles in the area of product management and product marketing, so it was interesting to read what Saeed Khan had to say on the subject in the following two posts (the first one in particular): http://labs.openviewpartners.com/role-of-product-marketing-in-your-startup-part-1/http://labs.openviewpartners.com/role-of-product-marketing-in-your-startup-part-ii/ These posts give really great insight in to what the different…

-

Are you doing marketing or Marketing?

Very interesting post here from the start of this year, from Joshua Duncan: http://www.arandomjog.com/2012/01/the-end-of-product-marketing/ In it, Joshua describes how the role of Product Marketing Manager (PMM) is, essentially, moribund – not because the work done by these people isn’t required, but because these activities are rapidly being taken up by other individuals (Product Managers, MarComms…