Category: Process & Frameworks

-

Daoism and Marketing Planning

A pretentious title for a very short post. But it is relevant. One of the problems that I have hit over and over when managing a marketing department, is the confusion and difficulty with planning. Ignoring cliches like “Failing to plan is planning to fail”, genuinely what is the purpose of planning for say a…

-

How My Approach to Marketing Differs from the Standard Playbook

You need to do something different to be seen

-

Selling to the Boss

1. Awareness — How many SDMs are aware of your brand? The first question for any marketing team is simple but fundamental: who actually knows we exist? Awareness is about building mental availability among senior decision-makers (SDMs) — the people who influence budgets, sign contracts, or shape vendor lists. To grow awareness: The goal isn’t…

-

My weekly routine

I’ve noticed recently how the advent of AI tools has significantly changed my work routine during the course of the week. Historically, Monday morning has been “Well that was a nice weekend, what the hell was I doing at work?”. This then takes me to my scribbled notes about what I was working on and…

-

Stage 1 – getting set up: foundations of my AI-powered chatbot project

Over the past few months, I’ve been building something a bit different: a real-time AI-powered assistant designed to help me work better with my own content. The goal is to create a system that can scan and catalog documents, blog posts, audio recordings, and notes, then surface that information back to me as I need…

-

-

-

How to add ChatGPT to your own website

There are many stages of exploring ChatGPT: I’ll talk about the first four points here and then, in the next article, the last point. This is a considerably bigger task, so needs a post of its own. The end goal is to allow customers and potential customers to come to your site and ask questions…

-

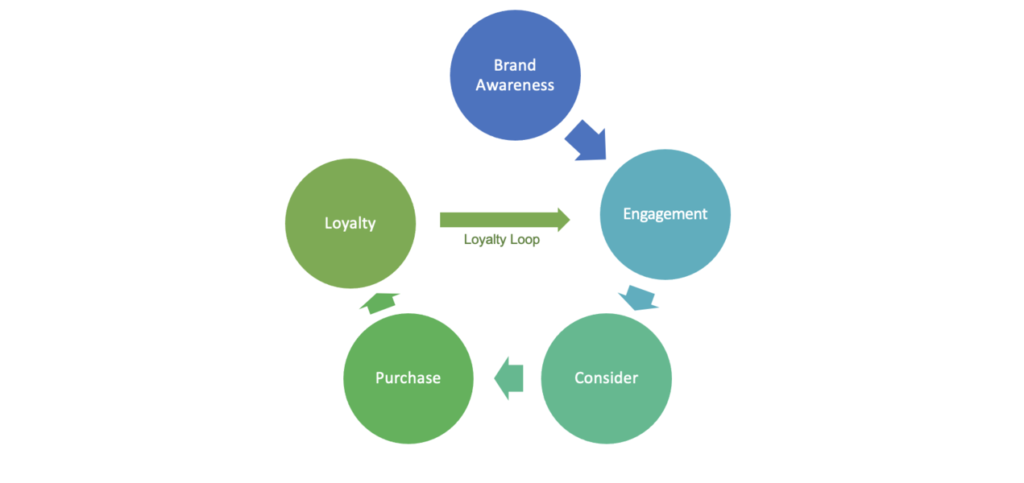

The marketing flywheel – an alternative to the marketing funnel

A lot has already been written about how the old marketing funnel model is no longer as relevant in modern B2B organisations as it used to be, and how a flywheel model is more appropriate for how customers really buy (as an old colleague said to me “The person who invented the marketing funnel should…

-

How to make decisions

There’s a myth that as you get more senior, you get to make more autonomous decisions about what happens in your business – what strategies to pursue, tools to buy, markets to go after and so on. “I’m the Head of Marketing, so surely I decide all the marketing stuff!?” In fact it’s the opposite…

-

Beware roles that advertise long hours

A friend is looking for a new role at the moment. He’s lucky enough to be able to pick and choose what he goes for, so I asked “What really attracts you to a job? What puts you off?”. It’s always interesting to know what people are looking for, how to genuinely attract great candidates…

-

Why ROI calculators aren’t enough

ROI calculators are a pretty common tool amongst B2B marketers. On the face of it, the logic is simple – show a calculation of how the time saved from subscribing to your product equates to money and how that money is less than the annual subscription cost charged. Then surely the sale should be in…

-

How Collaboration Can Grow Revenue

Why do Marketing and Sales departments need to collaborate? Sure, it’s nice, but beyond people getting on better together, how can it really impact the numbers, the outcomes for the business? We’ve just spent a month at Redgate improving the collaboration between the two departments and we can see the direct and measurable impact on…

-

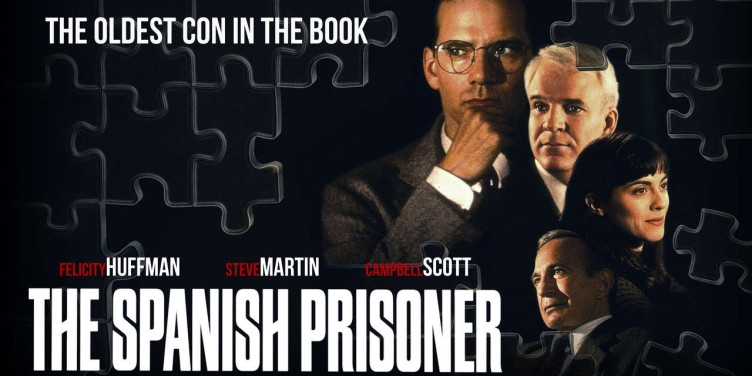

How to Present to an Exec or Board

For better or worse I find a lot of my tips and tricks for working in a software company from fiction books and films. I learnt most of what I know about how to present to senior folk (an Exec team or a Board even) from a two-minute scene in David Mamet’s film “The Spanish…

-

Focus on Marketing Effectiveness to Scale Up

Here’s a very non-theoretical problem – you’ve got two ways of spending some digital marketing budget, either a) LinkedIn advertising, or b) Facebook advertising. The former works pretty well, you manage to calculate a return of $1.50 for every dollar you spend. The Facebook adverts are more effective though – a return of $1.80 for…

-

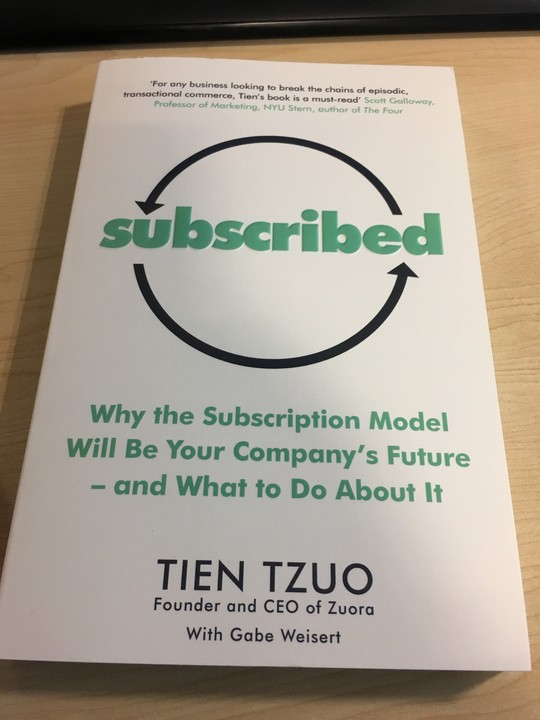

Review: “Subscribed” by Tien Tzuo

The Subscription Economy is the idea that more and more customers (and therefore vendors) are moving over to being subscribers of services rather than purchasers of products. An obvious example is Spotify – the money spent by consumers on streaming services now significantly outweighs revenue from physical CDs or even digital downloads: In 2019, more money is…

-

Sentiment Analysis of Twitter – Part 2 (or, Why Does Everyone Hate Airlines!?)

It took quite a while to write part 2 of this post, for reasons I’ll mention below. But like all good investigations, I’ve ended up somewhere different from where I thought I’d be – after spending weeks looking at the Twitter feeds for different companies in different industries, it seems that the way Twitter is…

-

There are Three Types of Marketing – Inbound, Outbound and… Plain Rude

Reading one of the many number of content marketing pieces from HubSpot, I noticed the following from a basic piece on What is Digital Marketing?, after paragraphs about the virtues of Inbound marketing techniques: Digital outbound tactics aim to put a marketing message directly in front of as many people as possible in the online…

-

Why Doing Nothing Inevitably Leads to Failure

Every new idea is a bad idea. Well, not quite, but every time you choose to do something new, there always seems to be 100 reasons why it’s going to fail. Wrong people, not enough people, misunderstanding of the market, can’t extract value from it, too many changes needed, not our core competence, not completely…

-

Why Complex Decisions Inevitably Take Weeks

I often find that, when it comes to make certain types of decision in an organisation, this just seems to take weeks. And if you’re unlucky, this can roll in to months. Why? What is it, a lack of decisiveness? An unwillingness to commit to anything? Lack of identification of a “Decision maker”? Just weakness!?…

-

Process Hawks and Doves

In US politics, and now politics around the world the terms “hawk” and “dove” (really “war hawk” and “war dove”) are used to identify politicians who have leanings in a particular direction – either towards controversial wars or against. The arguments always play out on both sides, hopefully tending towards a solid, well-argued solution for…

-

The Need to Constantly Change in Marketing

There’s a quote that I really like from one of Christopher Isherwood’s early novels, The Memorial: “Men always seem to me so restless and discontented in comparison to women. They’ll do anything to make a change, even when it leaves them worse off. […] Whereas […] we women, we only want peace.” Removing the sexism…

-

What I Should Be Doing as a Marketer. But Won’t Be

“Should” is a complicated – and dangerous – word in marketing. How many times have you read blogs and articles proclaiming that you “Should be doing more mobile marketing”, that you “Should have full content strategy”, that you “Should be creating personae for all of you target segments”, “Should be doing more on Twitter”? And…

-

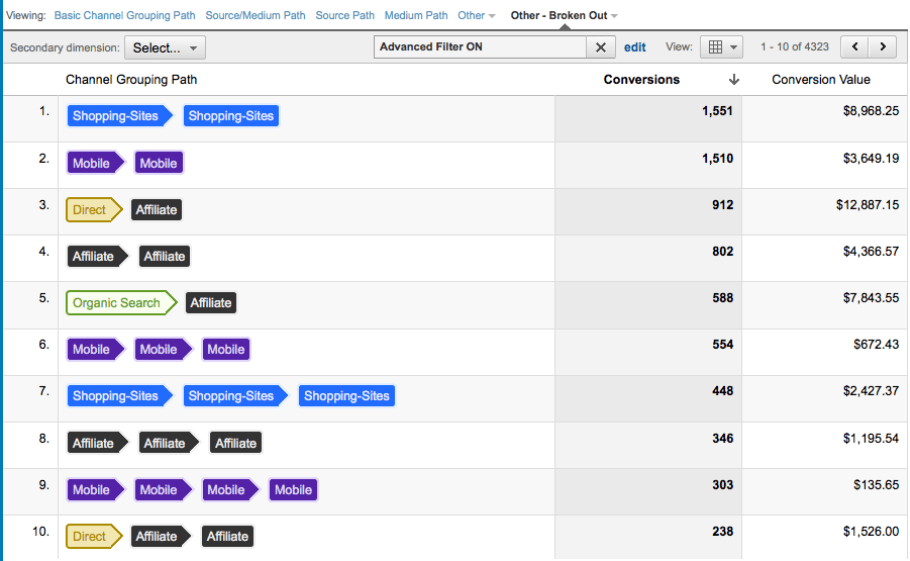

When Marketing Isn’t Really Marketing – Google Analytics Multi-Channel Funnels

I was excited this week about the prospect of finally having the time to play with Google Analytics’ advanced Multi-channel Funnel (MCF) functionality. As announced at their summit last year, they’ve extended their advanced attribution modelling to all GA users and this provides the opportunity to (finally!) try and attribute some measure of value to…

-

Lean Personas – How to Make Personas More Useful

First of all, I prefer the term “Personas” to “Personae”. Doesn’t “Personae” just seem pretentious, n’est-ce que pas? Anyway, the point is, I’ve always struggled, over the years, to find personas a useful tool in marketing. I’m specifically talking about marketing here, rather than user-centred design – I know these are two sides of the same coin,…