Category: Marketing Teams

-

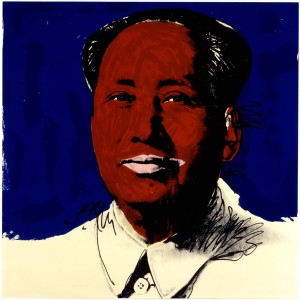

Dissecting Thought-Leadership

To start, I don’t really like the term “Thought-Leadership”. Like many things in marketing, it’s a bit too “marketing-ey”. It also has echoes of NLP, something I’m not a big fan of, to say the very least. But, I guess it’s pretty descriptive for what it means – I’d define it as something along the…

-

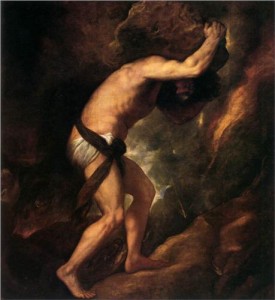

Working on the Coalface

Everyone who works in marketing and product management should be spending as much time as they possibly can with customers. Period. This is, of course, a bit of a bland and obvious statement (like all those marketing books that promise so much and deliver so little!) – we know this, we don’t have to be…

-

How To Measure Campaign Success

Quite a simple post this time round. Essentially how I measure the success of a given campaign or piece of marketing work. NB: This isn’t the Holy Grail of properly attributed marketing ROI – when I’ve worked that, I’ll post it up, if I haven’t retired first – but instead a framework for how to…

-

Is it the Content or the Author that Matters for a Blog?

If, like me, you subscribe to a lot of marketing RSS feeds, then you can’t have failed to notice the almost overwhelming proportion of posts about content marketing/SEO and how choosing appropriate and useful content for, say, your blog is a killer way of drawing in early stage leads. This SEOMoz post is a good…

-

Product Marketing and Product Management Roles

I wrote a brief post, about the different roles in the area of product management and product marketing, so it was interesting to read what Saeed Khan had to say on the subject in the following two posts (the first one in particular): http://labs.openviewpartners.com/role-of-product-marketing-in-your-startup-part-1/http://labs.openviewpartners.com/role-of-product-marketing-in-your-startup-part-ii/ These posts give really great insight in to what the different…

-

Are you doing marketing or Marketing?

Very interesting post here from the start of this year, from Joshua Duncan: http://www.arandomjog.com/2012/01/the-end-of-product-marketing/ In it, Joshua describes how the role of Product Marketing Manager (PMM) is, essentially, moribund – not because the work done by these people isn’t required, but because these activities are rapidly being taken up by other individuals (Product Managers, MarComms…