Category: Marketing Teams

-

Focus on quality – lessons from Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Introduction What is “quality” content? If you’ve ever read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig, you’ll know his reflections on craftsmanship go far beyond fixing bikes. As he wrote: “[In a craftsman], the material and his thoughts are changing together in a progression of changes until his mind’s at rest at…

-

-

Why company culture is so important in marketing

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast“ Such a well known quote, it barely needs a reference (but I will do anyway – it’s Peter Drucker). One of my side projects is an attempt at taking all of my own knowledge from the last few years of marketing and putting them into an AI model. One of…

-

-

How to conduct customer interviews

I’ve created a new guide on how to run a customer interview tour. Download from below:

-

Remove meetings to achieve true flow

It’s been a great first few weeks at Syskit. I’ve really enjoyed it, and I’ve loved meeting the team. But more than this, I can directly see why the company is going to keep growing at an even faster pace than it has so far. Why? Is it the product? Is it the strategy? The…

-

Speed

I’ve worked on projects where there has been a tenfold difference in the productivity of the teams. Specifically, given a piece of work like “Let’s build a new campaign” or “Let’s redesign the homepage”, I’ve seen the same team size do that in one week or in 10 weeks. What was that difference? Specific processes?…

-

Have a plan. But double down on what’s working

There are always too many things to do running a marketing department. The essence of your job as a marketing leader is making strategic choices about where to double down and where to pause. This is what makes the job both interesting and difficult. Below I’ve provided a scorecard that I’ve used many times in…

-

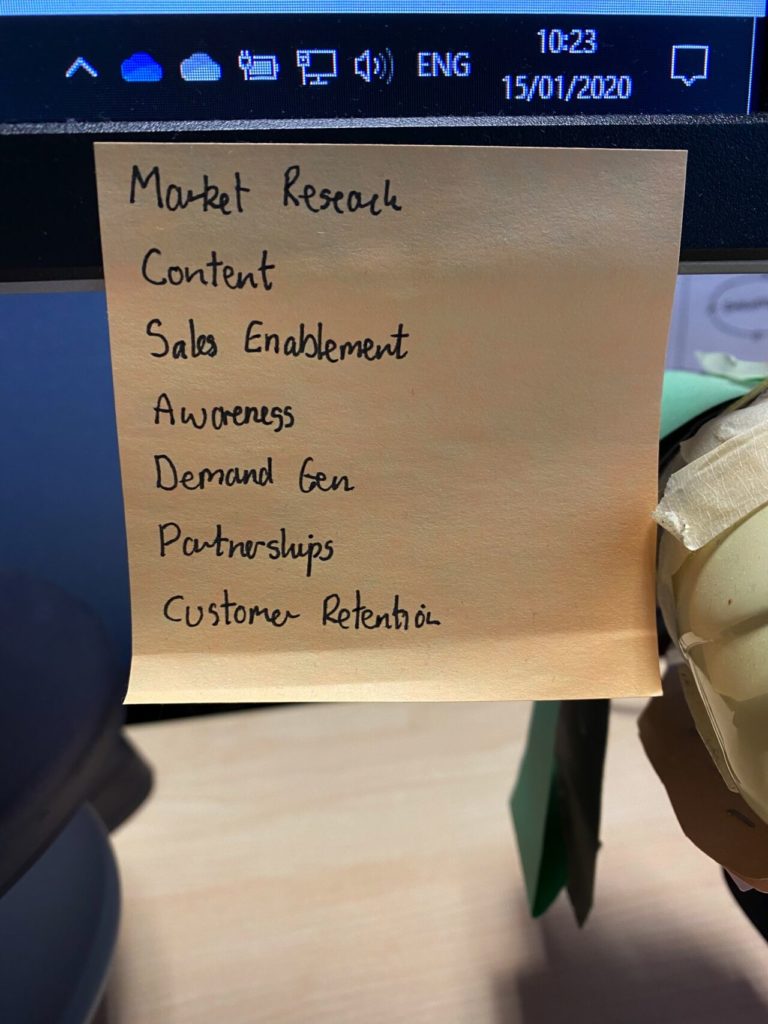

Strategic marketing – knowing where to place your bets

Strategy is about making choices. If you’re not stopping some activities or choosing to not do something then you’re not being strategic. Easy to say, less easy to implement, particularly when the organisation wants “More leads, more leads, more leads!”. How do you say “I want to do less”? Almost everything in the world of…

-

-

B2B marketing help

One thing I learned very early on in my career – you can’t do a marketing job without almost constant interaction with the rest of the business. Whether that’s the sales team, the product team, HR or anyone else, you need constant input and feedback from both inside and outside the building. One very specific…

-

Creating a marketing strategy plan

What should be in the plan? When I moved into the CMO role I realised a number of ways in which the position was different to what I had done previously. A lot of these differences are to do with being in a C-level role, but I’ll focus here on the CMO position and the…

-

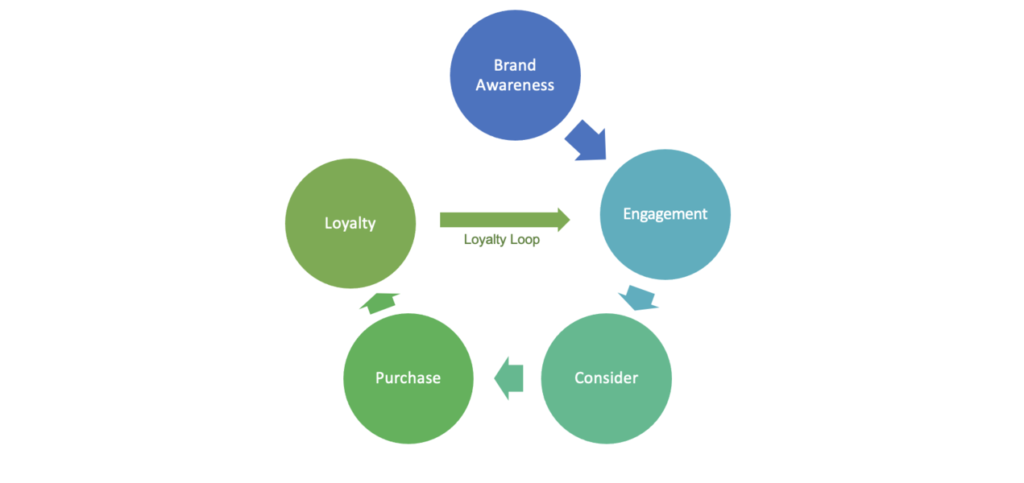

The marketing flywheel – an alternative to the marketing funnel

A lot has already been written about how the old marketing funnel model is no longer as relevant in modern B2B organisations as it used to be, and how a flywheel model is more appropriate for how customers really buy (as an old colleague said to me “The person who invented the marketing funnel should…

-

How to make decisions

There’s a myth that as you get more senior, you get to make more autonomous decisions about what happens in your business – what strategies to pursue, tools to buy, markets to go after and so on. “I’m the Head of Marketing, so surely I decide all the marketing stuff!?” In fact it’s the opposite…

-

Beware roles that advertise long hours

A friend is looking for a new role at the moment. He’s lucky enough to be able to pick and choose what he goes for, so I asked “What really attracts you to a job? What puts you off?”. It’s always interesting to know what people are looking for, how to genuinely attract great candidates…

-

Why ROI calculators aren’t enough

ROI calculators are a pretty common tool amongst B2B marketers. On the face of it, the logic is simple – show a calculation of how the time saved from subscribing to your product equates to money and how that money is less than the annual subscription cost charged. Then surely the sale should be in…

-

Scaling from SMBs to the Enterprise – a 10-Point Plan

I’ve had this conversation about 6 times in the last year – how can you scale from selling to small businesses (SMBs), up to Enterprise organisations? What are the marketing challenges? What’s necessary, what’s nice-to-have, and what’s a red herring? This is something we’ve done incredibly well at Redgate over the last five years (from…

-

How We Grew Marketing Sourced Pipeline by 20% in One Quarter

We’re about to go into our quarterly review period at Redgate. We don’t just run QBRs, we also run reviews across all parts of the business. These are a chance to examine the last three months – what worked? What’s going well? What’s not going well and needs fixing? All part of a strong agile…

-

How Collaboration Can Grow Revenue

Why do Marketing and Sales departments need to collaborate? Sure, it’s nice, but beyond people getting on better together, how can it really impact the numbers, the outcomes for the business? We’ve just spent a month at Redgate improving the collaboration between the two departments and we can see the direct and measurable impact on…

-

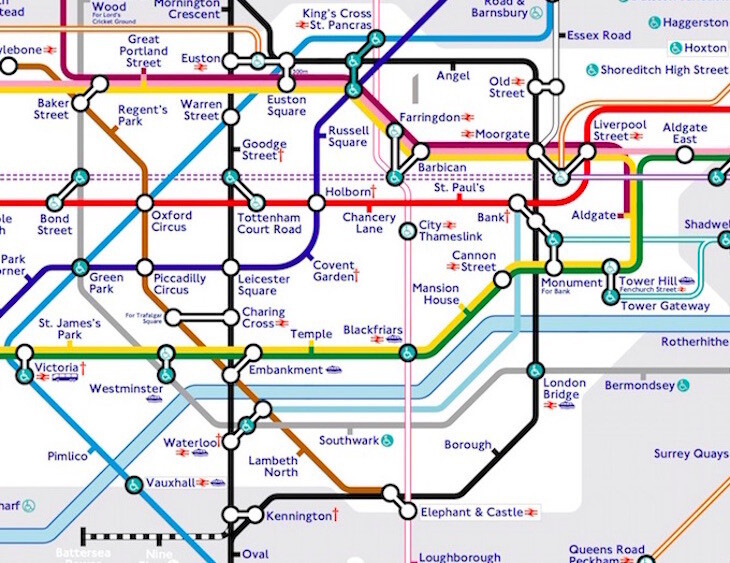

Getting from Green Park to King’s Cross

Anyone who has used the London tube system much, will know that there are two routes from Green Park to King’s Cross – the Victoria Line and the Piccadilly Line. The Victoria Line is the “Right” way to get from Green Park to KX – it’s quicker with fewer stops, why wouldn’t you take this…

-

Working from Home

Lots of people have written about the “New world of remote working” (so much so, that that phrase has become a cliche in the space of six months). But I think it’s still an interesting topic, because I have a hunch the changes we’ve seen in 2020 will become permanent, even as we start to…

-

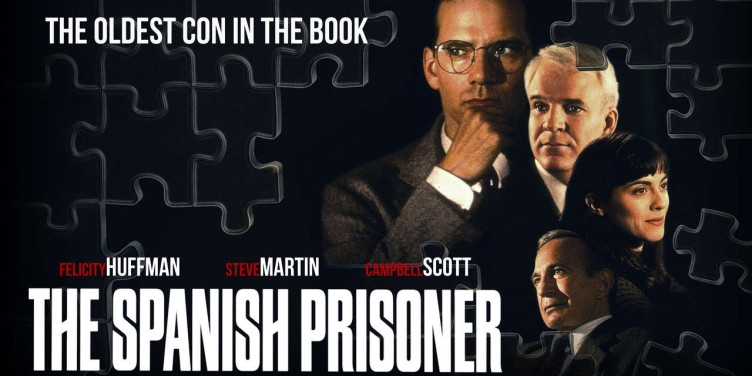

How to Present to an Exec or Board

For better or worse I find a lot of my tips and tricks for working in a software company from fiction books and films. I learnt most of what I know about how to present to senior folk (an Exec team or a Board even) from a two-minute scene in David Mamet’s film “The Spanish…

-

Join a Scaleup to Scale Your Career

It’s hard getting ahead in Marketing. It’s a discipline changing every year (certainly true of 2020), it covers an enormous breadth of disciplines which need a great variety of skills and it’s notoriously difficult to prove the impact of your work. So what can you do to give yourself the best chance of success? Of…

-

Under-promise, Over-deliver for product-led growth

There’s a lot written about the advantages of product-led growth (PLG), how it keeps marketing and sales costs down, how customers prefer it and so on. All good, but I struggled to find much on the actual strategies to use – how do you do it? There are obvious things like having a product with amazing product-market…

-

External Marketing during COVID-19

Everyone’s got marketing advice about what to do in the current crisis, haven’t they? As though it’s easy and obvious what you should be doing in this “first-in-a-lifetime” situation we find ourselves in?! I don’t think it’s easy and obvious at all. But if you work in marketing, now is the time to earn your…

-

Focus on Marketing Effectiveness to Scale Up

Here’s a very non-theoretical problem – you’ve got two ways of spending some digital marketing budget, either a) LinkedIn advertising, or b) Facebook advertising. The former works pretty well, you manage to calculate a return of $1.50 for every dollar you spend. The Facebook adverts are more effective though – a return of $1.80 for…

-

Finding Balance in Marketing Strategy

It’s that time of year again (for us anyway) – putting together the detailed marketing strategy and plan for 2021. And yet again it’s hard going. I’m not complaining – if it’s not difficult, then you’re not doing it right. Our job as marketing leaders is to work through the almost-overwhelming volume of data and…

-

Why HR is the Most Important Department in your Business

Surely not!? Surely it’s the Marketing department (I am a marketer after all)? Or maybe Sales, maybe Engineering, maybe Customer Support. But no, I want to argue that getting HR right is one of the step changes you can make to a business, with far broader impact than any of the areas listed above. There…

-

Your Customers Pay Your Salary (not your Employer)

“Don’t find customers for your products, find products for your customers” – Seth Godin The simplest ideas are the best. But they can also seem the most banal. Hidden in the Seth Godin quote above is, I believe, one of the key differences between a mature and immature organisation. Between a company that is ready…

-

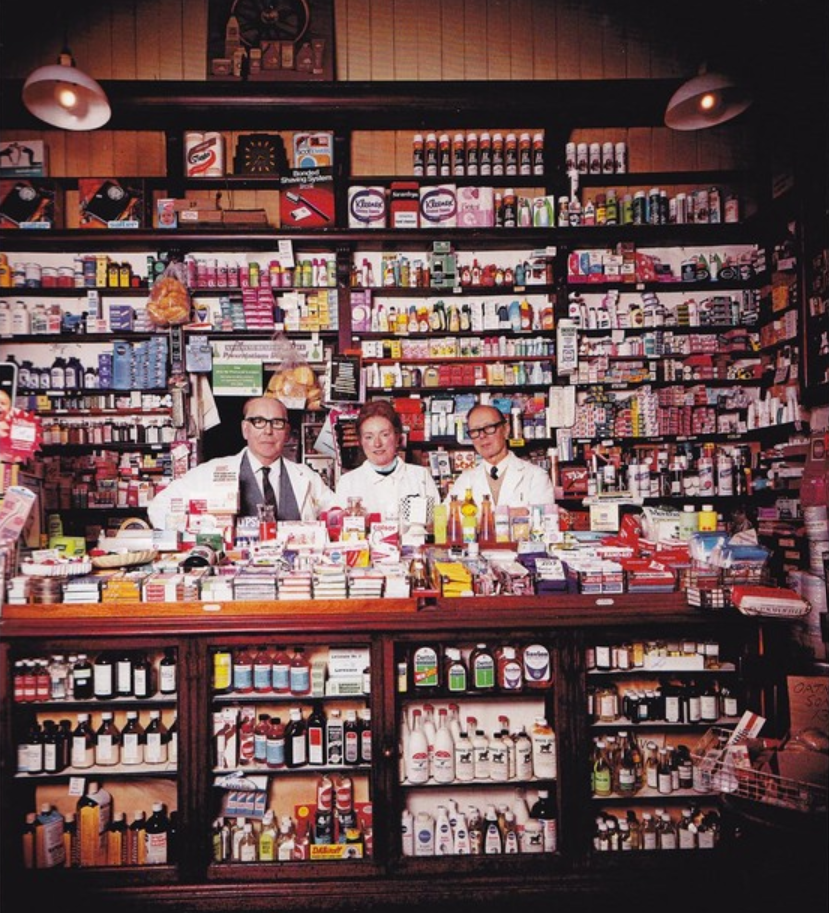

To learn about the “Buyer Process” try buying something

I guess this is more a post about sales rather than marketing per se, but still – understanding buyer journeys and how you can help at different stages is an important part of the marketing role, particularly when the sales cycle is complex. I’ve read quite a lot about marketing funnels – how customers at…

-

Your Primary Job as a Marketing Leader is to Prioritise

I’ve just finished the excellent Complete Guide to B2B Marketing by Kim Ann King. It’s very “List-ey” – it’s full of To Do lists (“Want to figure out your budgets for media spend? Here’s a 7-point list of how to do it”), which I really like. Many marketing books are rather waffly and vague, so a…

-

Measuring Customer Experience

Customer Experience (CX) – it’s a popular topic right now, analogous to the importance of User Experience (UX) in the world of product development. And something which I strongly believe is important for a marketing team to get right. So, we all know that getting your Customer Experience great and consistent is important for all of…

-

If a Brewery Can Innovate, So Can You

This weekend we went to Southwold and Aldeburgh – two of my favourite places in the UK, for various reasons. One of these reasons is the Adnams Brewery, based in Southwold. It’s been going for over a century and has always produced wonderful beer (as well as other drinks). But a few years ago I…

-

People. Customers. Action.

I was mugging up again last week on the McKinsey 7-S Model, now pretty old, but I still think a great framework for looking at organisational effectiveness. All very interesting, but then I found the post that Tom Peters wrote about the book decades later and found a quote that I particularly liked: “You could boil…

-

Why You Can’t Pivot as Quickly as You’d Like

There’s a great scene, towards the end of the film American Sniper, where Bradley Cooper’s character has to take a shot from over a mile away from his target. But the point is, there’s a long time between the point he takes his shot, and when he finds out if he has hit or not.…

-

Better to be in the Arena Fighting…

A place I used to work, perhaps 10-12 years ago, had (what I think, now) was a strange custom. Every Monday morning the whole company would get together to go through everything. There were around 70 of us, at the peak, and we would all stand around from about one-and-a-half hours going through sales, marketing, development, ops,…

-

The Difference Between Management and Leadership

What is the essential difference between “Management” and “Leadership”? Are these, basically the same thing – “The stuff you do when you get “Manager” in your job title somewhere? These are both such vague, all-encompassing terms (perhaps the worst job title for this is “General Manager” – it sounds like you “just do stuff” not…

-

The Value of Completely Arbitrary and Artificial Constraints

Another slightly abstract post today, though based on very real and pragmatic problems. When working on a project, where there are 100s of different options for things you can do and you’re drifting in to option paralysis, often a manager will use a deadline (for example, an event, or a customer demo) as a way…

-

Great Customer Service – Detail, Memory and Management

I was fortunate enough this week to go for one of the finest meals of my life. Just incredible food – however, that’s not what this post is about (I believe there are many blogs out there on all things foodie..). It’s about the superb customer service that came with the meal and the elements…

-

Why Doing Nothing Inevitably Leads to Failure

Every new idea is a bad idea. Well, not quite, but every time you choose to do something new, there always seems to be 100 reasons why it’s going to fail. Wrong people, not enough people, misunderstanding of the market, can’t extract value from it, too many changes needed, not our core competence, not completely…

-

Why Complex Decisions Inevitably Take Weeks

I often find that, when it comes to make certain types of decision in an organisation, this just seems to take weeks. And if you’re unlucky, this can roll in to months. Why? What is it, a lack of decisiveness? An unwillingness to commit to anything? Lack of identification of a “Decision maker”? Just weakness!?…

-

Setting Ambitious Marketing Targets is a Waste of Time

We all, periodically set targets for ourselves and/or other marketing folk. How often have we started the year with a plan that goes something like this: Do activities a, b and c, Through activities a, b and c, achieve the following “up-and-to-the-right”* targets: Great, we’re all rich! But what I want to argue is there…

-

Process Hawks and Doves

In US politics, and now politics around the world the terms “hawk” and “dove” (really “war hawk” and “war dove”) are used to identify politicians who have leanings in a particular direction – either towards controversial wars or against. The arguments always play out on both sides, hopefully tending towards a solid, well-argued solution for…

-

The Need to Constantly Change in Marketing

There’s a quote that I really like from one of Christopher Isherwood’s early novels, The Memorial: “Men always seem to me so restless and discontented in comparison to women. They’ll do anything to make a change, even when it leaves them worse off. […] Whereas […] we women, we only want peace.” Removing the sexism…

-

The End of the Marketing Plan

I’ve read a couple of books in the last year both with something to say on the subject of marketing plans. Well, I’ve read one and given up on the other. The one I finished was: Lean Enterprise by Jez Humble, Barry O’Reilly and Joanne Molesky And the one I barely got started on was:…