Category: Leadership

-

My 10 Biggest Marketing Screw-ups of 2013

It’s nearing Christmas, time for “Top 10…” and “Round up of 2013″ style posts, so here’s mine. One of my failings is that I’m a terrible self-critic, so I thought I’d write a piece on “My 10 biggest marketing screw-ups this year”. I don’t think I’ll get fired because luckily I work at a place…

-

Market Sizing – Old vs. New Markets

I was attempting some market sizing activity this week. It’s something I haven’t done for a few months and quite frankly I’d forgotten how hard it was. I start from a premise that the future is completely unpredictable. Really, aren’t we kidding ourselves when we think we can predict how many people will buy our…

-

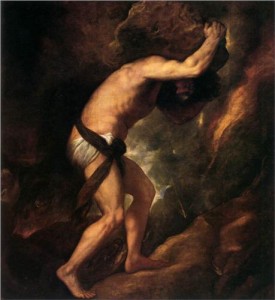

Working on the Coalface

Everyone who works in marketing and product management should be spending as much time as they possibly can with customers. Period. This is, of course, a bit of a bland and obvious statement (like all those marketing books that promise so much and deliver so little!) – we know this, we don’t have to be…

-

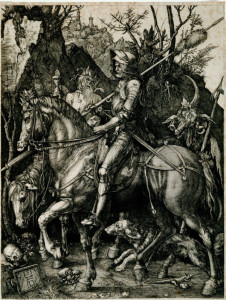

What I Should Be Doing as a Marketer. But Won’t Be

“Should” is a complicated – and dangerous – word in marketing. How many times have you read blogs and articles proclaiming that you “Should be doing more mobile marketing”, that you “Should have full content strategy”, that you “Should be creating personae for all of you target segments”, “Should be doing more on Twitter”? And…

-

SaaS Product Management, Lovefilm and Getting Stale

Lovefilm have just revamped the app that is used by devices such as Blu-ray players and the PS3 and it is, in my opinion, a great improvement. There are a large number of changes but I think also, and I’m speculating massively here, that the improvements were heavily shaped by some great data driven product…

-

Competition, Disruptive Innovation and Total Recall

A key part of any product marketing role is analysing the competition for your product. Put simply, when your potential customers are looking to solve a particular problem or take advantage of an opportunity, what are the options that they see, one of which (hopefully!) is you? Sometimes this job is easy when you have…

-

New Year, New Markets, New Products

Many of us will have come back after the Christmas break trying to think of new activities, new ideas and new opportunities for 2013. One of these is – is there some new product, proposition or market we could address, obviously with a view to expanding the addressable market, or creating new revenue streams? Easy,…

-

Are you doing marketing or Marketing?

Very interesting post here from the start of this year, from Joshua Duncan: http://www.arandomjog.com/2012/01/the-end-of-product-marketing/ In it, Joshua describes how the role of Product Marketing Manager (PMM) is, essentially, moribund – not because the work done by these people isn’t required, but because these activities are rapidly being taken up by other individuals (Product Managers, MarComms…