Category: Leadership

-

Daoism and Marketing Planning

A pretentious title for a very short post. But it is relevant. One of the problems that I have hit over and over when managing a marketing department, is the confusion and difficulty with planning. Ignoring cliches like “Failing to plan is planning to fail”, genuinely what is the purpose of planning for say a…

-

Whitepaper on How to Optimise for AEO and GEO

Download for free! Below are the details of 2-month experiment I undertook, to understand what affects AI answers in ChatGPT, Gemini, Perplexity, Copilot and Google.

-

How My Approach to Marketing Differs from the Standard Playbook

You need to do something different to be seen

-

Focus on quality – lessons from Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Introduction What is “quality” content? If you’ve ever read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig, you’ll know his reflections on craftsmanship go far beyond fixing bikes. As he wrote: “[In a craftsman], the material and his thoughts are changing together in a progression of changes until his mind’s at rest at…

-

Building an AI assistant to help do the work I love

“If your job isn’t what you love, then something isn’t right” 1 If you are not passionate or at least interested in what your company does for customers then working in marketing is quite a slog. Of course parts of the marketing role which are less interesting than other parts (I’m no fan of doing…

-

Marketing Pyramid v3 – updated marketing model

I’ve updated my marketing pyramid, adding in a new layer for LLMOs – I feel it has got to a point where a marketing strategy that doesn’t reference this new world will start to look a little dated. I’m working on a new version of this pyramid which property understands the impact of LLM developments,…

-

My weekly routine

I’ve noticed recently how the advent of AI tools has significantly changed my work routine during the course of the week. Historically, Monday morning has been “Well that was a nice weekend, what the hell was I doing at work?”. This then takes me to my scribbled notes about what I was working on and…

-

Why company culture is so important in marketing

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast“ Such a well known quote, it barely needs a reference (but I will do anyway – it’s Peter Drucker). One of my side projects is an attempt at taking all of my own knowledge from the last few years of marketing and putting them into an AI model. One of…

-

Making decisions in a Bayesian world

Most of your time as a marketing leader is spent trying to make decisions with inadequate data. In an ideal world, we would have run an A/B test on everything we wanted to do, looked at the numbers and then made a decision. Which image should we use for our new advert? What message? What…

-

-

How to conduct customer interviews

I’ve created a new guide on how to run a customer interview tour. Download from below:

-

Slaying a few marketing myths

We’ve been doing some digital marketing work recently and the more and more time I spend on digital work the more beasts I feel need to be slain. NB: I’m talking specifically about B2B marketing here – which is important. It’s important because many of the problems that B2B marketers face come from taking a…

-

Remove meetings to achieve true flow

It’s been a great first few weeks at Syskit. I’ve really enjoyed it, and I’ve loved meeting the team. But more than this, I can directly see why the company is going to keep growing at an even faster pace than it has so far. Why? Is it the product? Is it the strategy? The…

-

Speed

I’ve worked on projects where there has been a tenfold difference in the productivity of the teams. Specifically, given a piece of work like “Let’s build a new campaign” or “Let’s redesign the homepage”, I’ve seen the same team size do that in one week or in 10 weeks. What was that difference? Specific processes?…

-

Have a plan. But double down on what’s working

There are always too many things to do running a marketing department. The essence of your job as a marketing leader is making strategic choices about where to double down and where to pause. This is what makes the job both interesting and difficult. Below I’ve provided a scorecard that I’ve used many times in…

-

Strategic marketing – knowing where to place your bets

Strategy is about making choices. If you’re not stopping some activities or choosing to not do something then you’re not being strategic. Easy to say, less easy to implement, particularly when the organisation wants “More leads, more leads, more leads!”. How do you say “I want to do less”? Almost everything in the world of…

-

B2B marketing help

One thing I learned very early on in my career – you can’t do a marketing job without almost constant interaction with the rest of the business. Whether that’s the sales team, the product team, HR or anyone else, you need constant input and feedback from both inside and outside the building. One very specific…

-

The Marketing Flywheel

New Year, new marketing plans. Hopefully by now you’ve kicked off various activities and you’re waiting to see how those early campaigns are working out. The other thing I see in marketing departments at this time though is burnout. Everyone is trying to do everything either because there’s no real strategy there (“let’s throw everything…

-

How to make decisions

There’s a myth that as you get more senior, you get to make more autonomous decisions about what happens in your business – what strategies to pursue, tools to buy, markets to go after and so on. “I’m the Head of Marketing, so surely I decide all the marketing stuff!?” In fact it’s the opposite…

-

How Collaboration Can Grow Revenue

Why do Marketing and Sales departments need to collaborate? Sure, it’s nice, but beyond people getting on better together, how can it really impact the numbers, the outcomes for the business? We’ve just spent a month at Redgate improving the collaboration between the two departments and we can see the direct and measurable impact on…

-

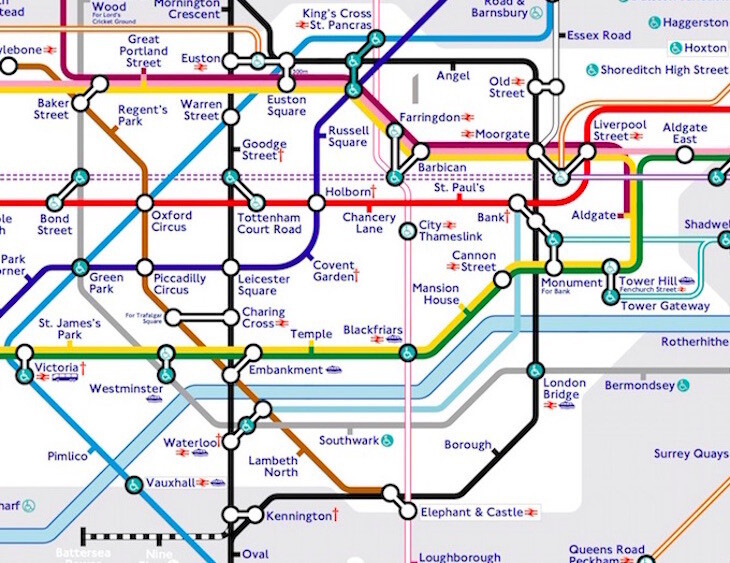

Getting from Green Park to King’s Cross

Anyone who has used the London tube system much, will know that there are two routes from Green Park to King’s Cross – the Victoria Line and the Piccadilly Line. The Victoria Line is the “Right” way to get from Green Park to KX – it’s quicker with fewer stops, why wouldn’t you take this…

-

How to Present to an Exec or Board

For better or worse I find a lot of my tips and tricks for working in a software company from fiction books and films. I learnt most of what I know about how to present to senior folk (an Exec team or a Board even) from a two-minute scene in David Mamet’s film “The Spanish…

-

Under-promise, Over-deliver for product-led growth

There’s a lot written about the advantages of product-led growth (PLG), how it keeps marketing and sales costs down, how customers prefer it and so on. All good, but I struggled to find much on the actual strategies to use – how do you do it? There are obvious things like having a product with amazing product-market…

-

Finding Balance in Marketing Strategy

It’s that time of year again (for us anyway) – putting together the detailed marketing strategy and plan for 2021. And yet again it’s hard going. I’m not complaining – if it’s not difficult, then you’re not doing it right. Our job as marketing leaders is to work through the almost-overwhelming volume of data and…

-

Your Customers Pay Your Salary (not your Employer)

“Don’t find customers for your products, find products for your customers” – Seth Godin The simplest ideas are the best. But they can also seem the most banal. Hidden in the Seth Godin quote above is, I believe, one of the key differences between a mature and immature organisation. Between a company that is ready…

-

To learn about the “Buyer Process” try buying something

I guess this is more a post about sales rather than marketing per se, but still – understanding buyer journeys and how you can help at different stages is an important part of the marketing role, particularly when the sales cycle is complex. I’ve read quite a lot about marketing funnels – how customers at…

-

You’re applying Marketing Theory, But You Don’t Even Know It

I love this article from Helen Edwards – about the need to understand marketing theory but then the need to apply it to the real world. Theory without execution is just an indulgence, a wholly academic pursuit. But if you’re executing well against a poor strategy, you’re just peddling fast in the wrong direction. She provides some…

-

Your Primary Job as a Marketing Leader is to Prioritise

I’ve just finished the excellent Complete Guide to B2B Marketing by Kim Ann King. It’s very “List-ey” – it’s full of To Do lists (“Want to figure out your budgets for media spend? Here’s a 7-point list of how to do it”), which I really like. Many marketing books are rather waffly and vague, so a…

-

If a Brewery Can Innovate, So Can You

This weekend we went to Southwold and Aldeburgh – two of my favourite places in the UK, for various reasons. One of these reasons is the Adnams Brewery, based in Southwold. It’s been going for over a century and has always produced wonderful beer (as well as other drinks). But a few years ago I…

-

Your People Are Your Customer Experience

We went to Milton Keynes today (school holidays – where else would you want to go?) and there were two examples of what I’d call, using marketing jargon, “A great customer experience” for the children. Listening to them talk about it afterwards, it wasn’t just something to do with the actual places we went to,…

-

People. Customers. Action.

I was mugging up again last week on the McKinsey 7-S Model, now pretty old, but I still think a great framework for looking at organisational effectiveness. All very interesting, but then I found the post that Tom Peters wrote about the book decades later and found a quote that I particularly liked: “You could boil…

-

Human Beings are Holding Back Machine Learning

Machine Learning (ML) and AI are big topics right now. Poor Lee Se-dol has just been beaten by AlphaGo – a machine put together by Google/DeepMind and there are numerous other examples in the news.So everyone is interested, and everyone wants to do more of it. Whether you work in marketing or any other discipline, there’s…

-

Why You Can’t Pivot as Quickly as You’d Like

There’s a great scene, towards the end of the film American Sniper, where Bradley Cooper’s character has to take a shot from over a mile away from his target. But the point is, there’s a long time between the point he takes his shot, and when he finds out if he has hit or not.…

-

Better to be in the Arena Fighting…

A place I used to work, perhaps 10-12 years ago, had (what I think, now) was a strange custom. Every Monday morning the whole company would get together to go through everything. There were around 70 of us, at the peak, and we would all stand around from about one-and-a-half hours going through sales, marketing, development, ops,…

-

The Difference Between Management and Leadership

What is the essential difference between “Management” and “Leadership”? Are these, basically the same thing – “The stuff you do when you get “Manager” in your job title somewhere? These are both such vague, all-encompassing terms (perhaps the worst job title for this is “General Manager” – it sounds like you “just do stuff” not…

-

The Value of Completely Arbitrary and Artificial Constraints

Another slightly abstract post today, though based on very real and pragmatic problems. When working on a project, where there are 100s of different options for things you can do and you’re drifting in to option paralysis, often a manager will use a deadline (for example, an event, or a customer demo) as a way…

-

Why Complex Decisions Inevitably Take Weeks

I often find that, when it comes to make certain types of decision in an organisation, this just seems to take weeks. And if you’re unlucky, this can roll in to months. Why? What is it, a lack of decisiveness? An unwillingness to commit to anything? Lack of identification of a “Decision maker”? Just weakness!?…

-

How Short Term Data Driven Decisions can be Dangerous in the Long Term

Jeff Bezos’s letters to shareholders are, of course, famous for their insight, not only in to how Amazon functions, but also for their advice on how to run a certain type of business. One of my favourite excerpts, from the 2005 letter is: As our shareholders know, we have made a decision to continuously and significantly…

-

Guerilla Marketing for Startups – An Example

We’re on holiday at the moment, in the Netherlands, but just thought I’d write a short post about a great example of guerilla marketing we spotted today, for something we visited whilst in The Hague. There’s a great attraction in a small basement near the centre of The Hague, called Amaze Escape – http://www.amaze-escape.com. Essentially…

-

Why Measuring Marketing ROI is Like Trying to Measure Employee ROI – Impossible!

I’m beginning to think I might need to change the tag line for this blog. One of my earliest posts was about how we needed to apply some scientific rigour to the process of marketing attribution and therefore ROI. How can marketers be getting away with such unproven and unprovable techniques, spending all this money…

-

Setting Ambitious Marketing Targets is a Waste of Time

We all, periodically set targets for ourselves and/or other marketing folk. How often have we started the year with a plan that goes something like this: Do activities a, b and c, Through activities a, b and c, achieve the following “up-and-to-the-right”* targets: Great, we’re all rich! But what I want to argue is there…

-

The Need to Constantly Change in Marketing

There’s a quote that I really like from one of Christopher Isherwood’s early novels, The Memorial: “Men always seem to me so restless and discontented in comparison to women. They’ll do anything to make a change, even when it leaves them worse off. […] Whereas […] we women, we only want peace.” Removing the sexism…

-

The End of the Marketing Plan

I’ve read a couple of books in the last year both with something to say on the subject of marketing plans. Well, I’ve read one and given up on the other. The one I finished was: Lean Enterprise by Jez Humble, Barry O’Reilly and Joanne Molesky And the one I barely got started on was:…

-

Xbox One vs. PS4 – How Marketing can Drive Development

Hard to miss it, but two next-gen gaming consoles were launched just before Christmas – Microsoft’s Xbox One, and the Playstation 4. Normally this sort of thing would pass me by (I’m not a big video game fan – they just seem like complete time vampires), but something I noticed was how interesting the two…

-

Dissecting Thought-Leadership

To start, I don’t really like the term “Thought-Leadership”. Like many things in marketing, it’s a bit too “marketing-ey”. It also has echoes of NLP, something I’m not a big fan of, to say the very least. But, I guess it’s pretty descriptive for what it means – I’d define it as something along the…