Category: Customer / ICP

-

-

-

-

Creating a marketing strategy plan

What should be in the plan? When I moved into the CMO role I realised a number of ways in which the position was different to what I had done previously. A lot of these differences are to do with being in a C-level role, but I’ll focus here on the CMO position and the…

-

Trying out ChatGPT

Of course, really, we all want to build Skynet. However, until Judgement Day comes, we’ll have to make do with ChatGPT. ChatGPT is obviously a Big Deal right now for marketers, so I wanted to find out for myself. Firstly, as a general point I do think it’s important to try technology out yourself before…

-

Scaling from SMBs to the Enterprise – a 10-Point Plan

I’ve had this conversation about 6 times in the last year – how can you scale from selling to small businesses (SMBs), up to Enterprise organisations? What are the marketing challenges? What’s necessary, what’s nice-to-have, and what’s a red herring? This is something we’ve done incredibly well at Redgate over the last five years (from…

-

Under-promise, Over-deliver for product-led growth

There’s a lot written about the advantages of product-led growth (PLG), how it keeps marketing and sales costs down, how customers prefer it and so on. All good, but I struggled to find much on the actual strategies to use – how do you do it? There are obvious things like having a product with amazing product-market…

-

There are two times when you don’t need to worry about Customer Success. And neither apply to you

Another thought exercise. I was trying to think of scenarios where Customer Success – i.e. genuinely worrying about whether your customers were using and getting value from your offering – wasn’t going to be a priority for a business in 2019. I could only think of two. But I think even these are slightly fatuous, I’d be…

-

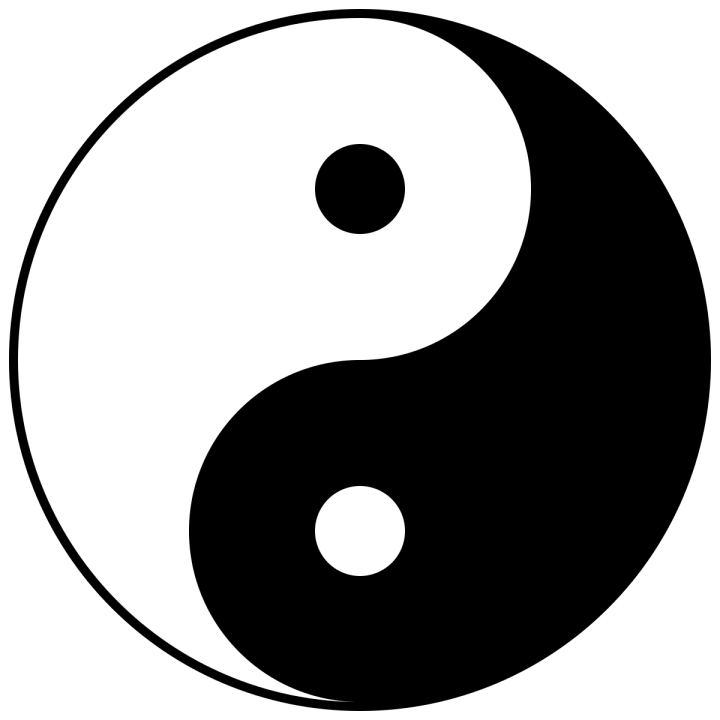

Finding Balance in Marketing Strategy

It’s that time of year again (for us anyway) – putting together the detailed marketing strategy and plan for 2021. And yet again it’s hard going. I’m not complaining – if it’s not difficult, then you’re not doing it right. Our job as marketing leaders is to work through the almost-overwhelming volume of data and…

-

Review: “Subscribed” by Tien Tzuo

The Subscription Economy is the idea that more and more customers (and therefore vendors) are moving over to being subscribers of services rather than purchasers of products. An obvious example is Spotify – the money spent by consumers on streaming services now significantly outweighs revenue from physical CDs or even digital downloads: In 2019, more money is…

-

Measuring Outbound vs. “Always-on” Marketing Performance

Whenever I meet customers I always slip in a marketing question or two along the lines of “Where did you hear about us? What brought you in to Redgate?”. One of the answers from a couple of months back was: Well a year ago, I got a new boss and she told me that I had…

-

Your Customers Pay Your Salary (not your Employer)

“Don’t find customers for your products, find products for your customers” – Seth Godin The simplest ideas are the best. But they can also seem the most banal. Hidden in the Seth Godin quote above is, I believe, one of the key differences between a mature and immature organisation. Between a company that is ready…

-

You’re applying Marketing Theory, But You Don’t Even Know It

I love this article from Helen Edwards – about the need to understand marketing theory but then the need to apply it to the real world. Theory without execution is just an indulgence, a wholly academic pursuit. But if you’re executing well against a poor strategy, you’re just peddling fast in the wrong direction. She provides some…

-

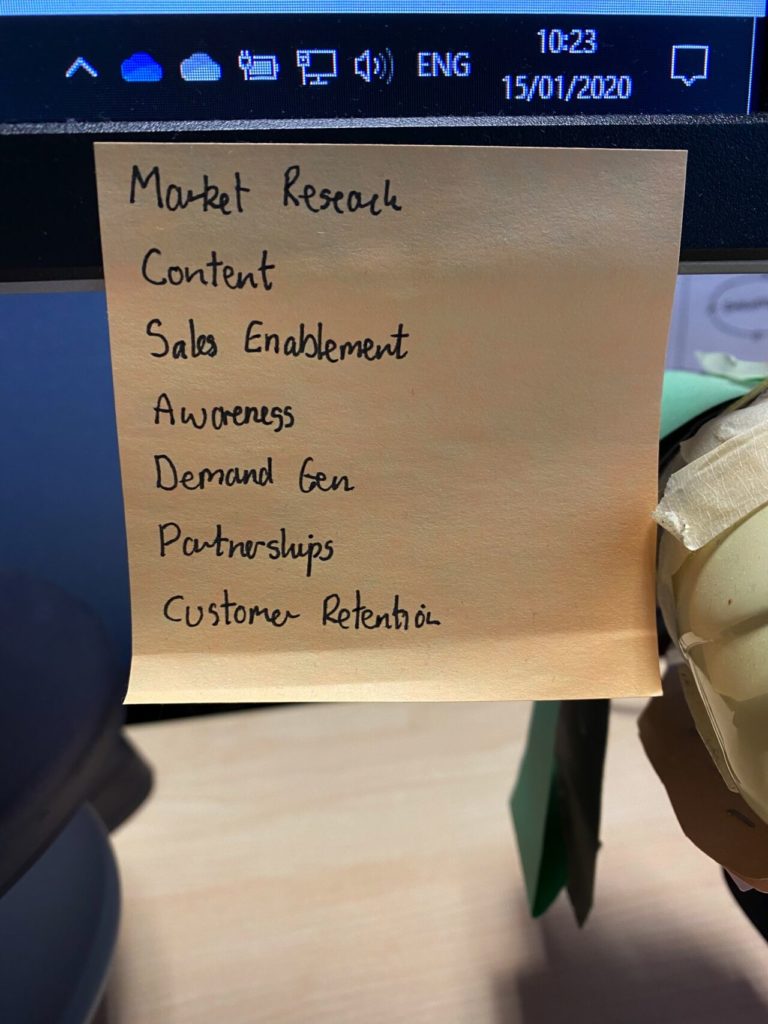

Your Primary Job as a Marketing Leader is to Prioritise

I’ve just finished the excellent Complete Guide to B2B Marketing by Kim Ann King. It’s very “List-ey” – it’s full of To Do lists (“Want to figure out your budgets for media spend? Here’s a 7-point list of how to do it”), which I really like. Many marketing books are rather waffly and vague, so a…

-

Write Content That People Actually Want to Read

This feels like a pointless blog post – the think I’m going to say seems so obvious, I shouldn’t need to say it. Still, I see examples where this doesn’t happen, so perhaps it’s worth re-iterating the point. Here’s the incredible insight – if you want people to read content that you write, then it…

-

Measuring Customer Experience

Customer Experience (CX) – it’s a popular topic right now, analogous to the importance of User Experience (UX) in the world of product development. And something which I strongly believe is important for a marketing team to get right. So, we all know that getting your Customer Experience great and consistent is important for all of…

-

People. Customers. Action.

I was mugging up again last week on the McKinsey 7-S Model, now pretty old, but I still think a great framework for looking at organisational effectiveness. All very interesting, but then I found the post that Tom Peters wrote about the book decades later and found a quote that I particularly liked: “You could boil…

-

Great Customer Service – Detail, Memory and Management

I was fortunate enough this week to go for one of the finest meals of my life. Just incredible food – however, that’s not what this post is about (I believe there are many blogs out there on all things foodie..). It’s about the superb customer service that came with the meal and the elements…

-

Increase Your Net Promoter Score to Decrease Marketing Spend

Marketing budgets are always on the squeeze. Or may be less that money is tight and more that the expectations on Return on Marketing Investment (ROMI) are raised. “I don’t mind spend £50k on this campaign, but I want to know what return I got, or you won’t have £50k to splurge next year”. The…

-

Keeping an Eye on The Competition

Many, many years ago I studied psychology and one of the most interesting courses I did was on development psychology – how we go from babies to infants to toddlers to children to teenagers to adults. The most fascinating lecture series was on Theory of Mind – the notion that, as we grow up we…

-

Xbox One vs. PS4 – How Marketing can Drive Development

Hard to miss it, but two next-gen gaming consoles were launched just before Christmas – Microsoft’s Xbox One, and the Playstation 4. Normally this sort of thing would pass me by (I’m not a big video game fan – they just seem like complete time vampires), but something I noticed was how interesting the two…

-

Working on the Coalface

Everyone who works in marketing and product management should be spending as much time as they possibly can with customers. Period. This is, of course, a bit of a bland and obvious statement (like all those marketing books that promise so much and deliver so little!) – we know this, we don’t have to be…

-

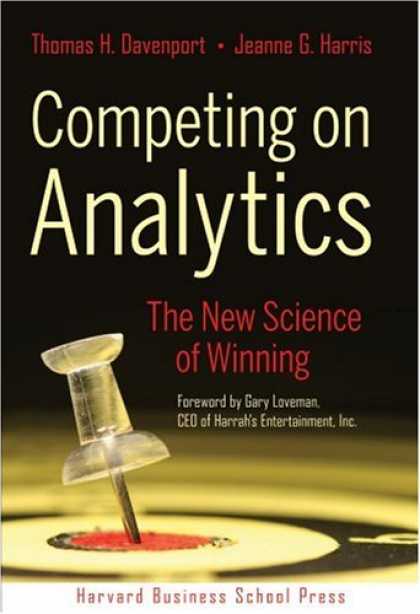

Five Tips for Implementing Marketing Analytics

The book Competing on Analytics by Thomas Davenport and Jeanne Harris is a short but very interesting read about the need for organisations to significantly improve their analytical capabilities if they want to compete in the modern marketplace. The argument, quoting directly from the author is that: In today’s global and highly interconnected business environment,…

-

New Year, New Markets, New Products

Many of us will have come back after the Christmas break trying to think of new activities, new ideas and new opportunities for 2013. One of these is – is there some new product, proposition or market we could address, obviously with a view to expanding the addressable market, or creating new revenue streams? Easy,…

-

Lean Personas – How to Make Personas More Useful

First of all, I prefer the term “Personas” to “Personae”. Doesn’t “Personae” just seem pretentious, n’est-ce que pas? Anyway, the point is, I’ve always struggled, over the years, to find personas a useful tool in marketing. I’m specifically talking about marketing here, rather than user-centred design – I know these are two sides of the same coin,…