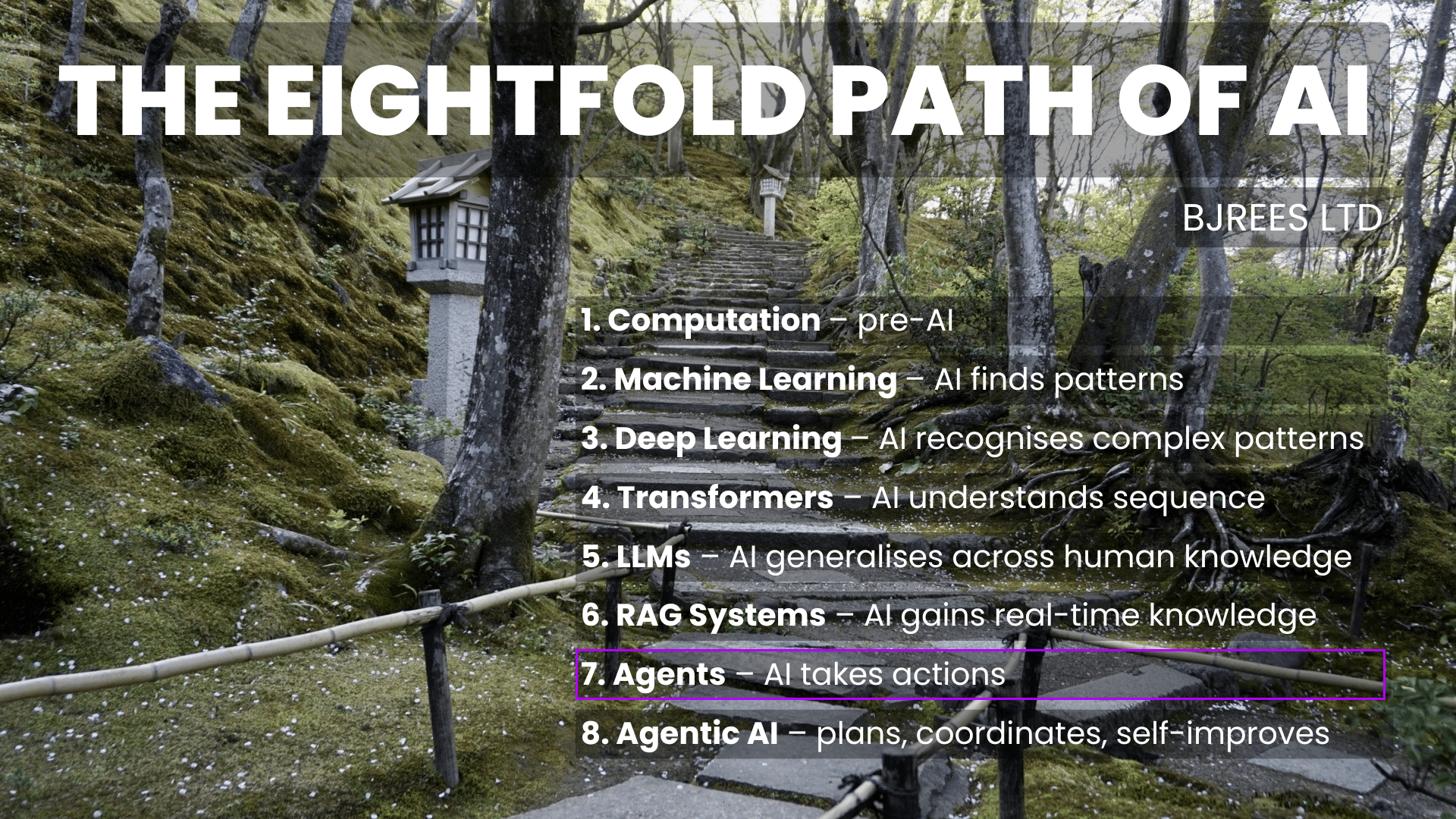

Step Seven – Agents: Orchestration and Controlled Action

By the time large language models matured (see The Eightfold Path of AI – Step 6), they could write, summarise, translate, and reason with surprising fluency. This is the positive and negative that most people see today – depending on realm, some incredibly impressive results in some situations, but of course also some slop and often hallucinations.

With retrieval and tool use, they could even operate beyond text: calling APIs, running code, and interacting with real systems. But in practice, these “agentic” capabilities were still fragile. This limitation was not raw intelligence. It was control.

Once you move beyond single prompts into multi-step work, you immediately hit practical questions: What is the task? What state are we in? What has already been done? What should happen next? How do we prevent loops, duplication, or silent failure? Without clear structure, agent behaviour becomes hard to predict, hard to debug, and hard to trust.

Stage Seven is the point where agents become systems.

This stage introduces orchestration: an explicit workflow around the model that manages tasks, routes work to the right agent, tracks state, and enforces execution boundaries. It does not make the AI “more autonomous”. It makes it more operational – capable of completing work reliably, one controlled step at a time.

Stage 7 is not the moment where machines “run free”. It is the opposite: it is where we design the scaffolding that keeps them safe, inspectable, and useful. Later in stage 8 I will write more about the governance of these systems in particularly spending. Moving into Agentic AI, the need to keep an eye on spend and have proper governance, goes from being an interesting afterthought, to a crucial part of the system (no-one wants to give Skynet access to their bank accounts!).

Basic Orchestration

From Agentic Behaviour to Orchestrated Systems

Agents need orchestration to avoid chaos

Previously we introduced agents that could plan, act, and interact with tools. But those capabilities were still largely embedded inside the model loop itself. Each run stood alone. The system did not reliably remember what had already happened or what should happen next. Execution depended on the model “doing the right thing” at the right moment.

Stage Seven separates reasoning from execution.

At this stage, a separate control layer sits around the model to manage how work is done. Tasks are defined clearly, execution is visible, and the same steps can be repeated reliably (the core benefit I have found).

Agent orchestration introduces the ability to:

- define tasks explicitly rather than embedding them in prompts

- route tasks to specific agents based on intent or role (as seen in frameworks such as LangGraph and CrewAI)

- execute actions only when instructed, rather than running continuously or autonomously

- track task state across steps and runs, enabling inspection and recovery

- record outputs and decisions for inspection and debugging

- stop, resume, or rerun work deterministically – a requirement for operational systems

- keep humans in the execution loop by design, reflecting established human-in-the-loop system patterns used in production AI

Crucially, nothing here is autonomous. The system does not decide what to do next. It does not initiate work. It does not act without permission. Every transition is deliberate.

Stage 7 is about controlled action, not independent action (coming in stage 8).

Why Orchestration Became Necessary

Early agent systems were compelling because they appeared to “just work”. A single prompt could trigger planning, tool use, and execution in one flow. For demonstrations and experiments, this was often enough. But as soon as agents were used for real, multi-step work, the limitations became obvious. The issue was not intelligence – it was control.

As tasks became longer and more complex, systems increasingly relied on the model to remember what had already happened, what still needed to be done, and how different steps related to each other. When something went wrong, it was often unclear why. When something partially succeeded, it was difficult to continue safely. And when results mattered, reproducibility was weak.

In practice, this led to common failure modes:

- work being repeated because progress was not tracked

- tasks getting stuck or looping unexpectedly

- difficulty identifying which step failed and why

- limited ability to pause, inspect, or safely rerun work

- low confidence in outcomes that could not be reproduced

I personally found a lot of these things happening in early experimentation and test runs. Working with agents has enormous benefits of course but also adds a level of complexity that needs to be understood at an early stage.

NB: These are not bugs in language models. They are structural consequences of asking a probabilistic system to manage control flow on its own (arguably the first point where we are running into slightly riskier behaviour, something I address later on).

Orchestration emerged as a response to this reality. By moving task definition, execution control, and state tracking outside the model, agent systems became easier to reason about, safer to operate, and more reliable over time.

How This Appears in Practice

In practice, Stage Seven systems introduce a small but critical set of structural patterns around the model.

Tasks are defined explicitly, rather than embedded implicitly in prompts. Each task has an identity, a purpose, and a lifecycle. Execution happens deliberately, not continuously, and only when instructed. Outputs are captured, recorded, and made available for inspection.

Work is routed to specific agents based on intent or role, rather than handled by a single, general loop. Progress is tracked across steps and across runs, making it possible to stop, resume, or rerun work without starting from scratch.

Most importantly, humans remain in the loop by design. The system does not decide what to do next. It waits. Control is externalised, visible, and interruptible.

This structure does not make agents more autonomous. It makes them usable.

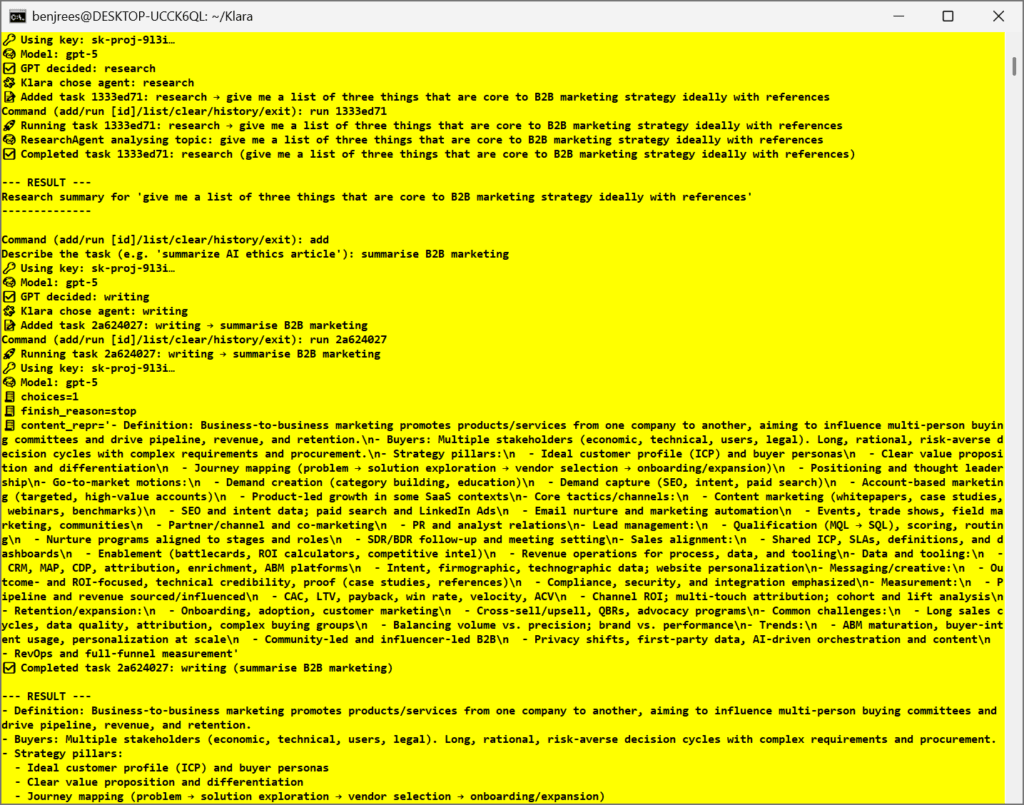

What Klara Is (Right Now)

At this stage, Klara – my AI agent code – is a deliberately constrained system.

It is a manual, human-in-the-loop agent orchestrator with:

- explicit task creation

- explicit execution

- LLM-mediated agent routing

- clean task state management

There is no background autonomy. Nothing runs unless instructed. Every task is created intentionally, executed deliberately, and recorded clearly.

This is not a limitation of the system. It is the defining characteristic of Stage 7.

Why Stage 7 Matters

Stage Seven represents a shift from experimentation to operation.

It moves agent systems:

- from clever demonstrations (ahem, what I’ve been doing up to this point) to dependable workflows

- from implicit behaviour to explicit control

- from model-managed flow to system-managed execution

This stage is where agents stop being interesting and start being trustworthy. It is where debugging becomes possible, where failures can be understood, and where results can be repeated.

Without this layer, scaling agent systems safely is extremely difficult.

Constraints and Open Tensions

Orchestration solves important problems, but it introduces its own trade-offs.

Keeping humans in the loop limits speed and scale. Explicit control adds friction. Manual task management does not feel “intelligent”, even when it is necessary.

These constraints are real. They are also intentional.

Stage 7 prioritises safety, clarity, and reliability over autonomy. It accepts friction in exchange for control. That tension is not a flaw – it is the boundary of the stage.

My Own Work at This Stage

New Year, New Stage

I spent a lot of the Twixmas period getting some simple AI agents up and running, in between mince pies. Going through the process was very revealing. The actual creation of agents isn’t particularly complicated, it is the following two steps which make the task interesting:

- The task of creating agents is simple, it is the orchestration of those agents which is more challenging. You immediately get into a world of complexity, trying to manage and understand the decisions that could be taken by the orchestration process. What makes this challenging is that it is happening in your absence. Normally when creating something new you are testing constantly to see that things are working but here you’re basically throwing something out there to see what it does!

- Money. Without controls this process becomes unbridled. For personal projects the payment for online models comes directly for me so it is obviously crucial to make sure I’m not accidentally over-spending. Most models have limits you can set (“Don’t spend more than $5 per day”), but do I trust them? Not yet. the need for some sort of AI governance is really important even before you start playing with Agentic AI.

Looking Ahead

Stage 7 gives agent systems the ability to coordinate work reliably.

Stage 8 asks a harder question: what happens when systems are allowed to decide when and how to act for themselves? Is that the point when Skynet becomes self aware?! 🙂

That transition is powerful, but it is also risky. Understanding Stage 7 clearly is a prerequisite for engaging with what comes next…

Summary

- Stage Seven introduces orchestration: structured coordination of agents, tasks, and execution.

- Agents operate within explicit workflows, with defined task boundaries and controlled sequencing.

- Human-in-the-loop control ensures predictability, observability, and safe operation.

- State, history, and task progress become explicit system concerns rather than implicit context.

- This stage enables reliable multi-step action without autonomy, self-initiation, or self-directed behaviour.