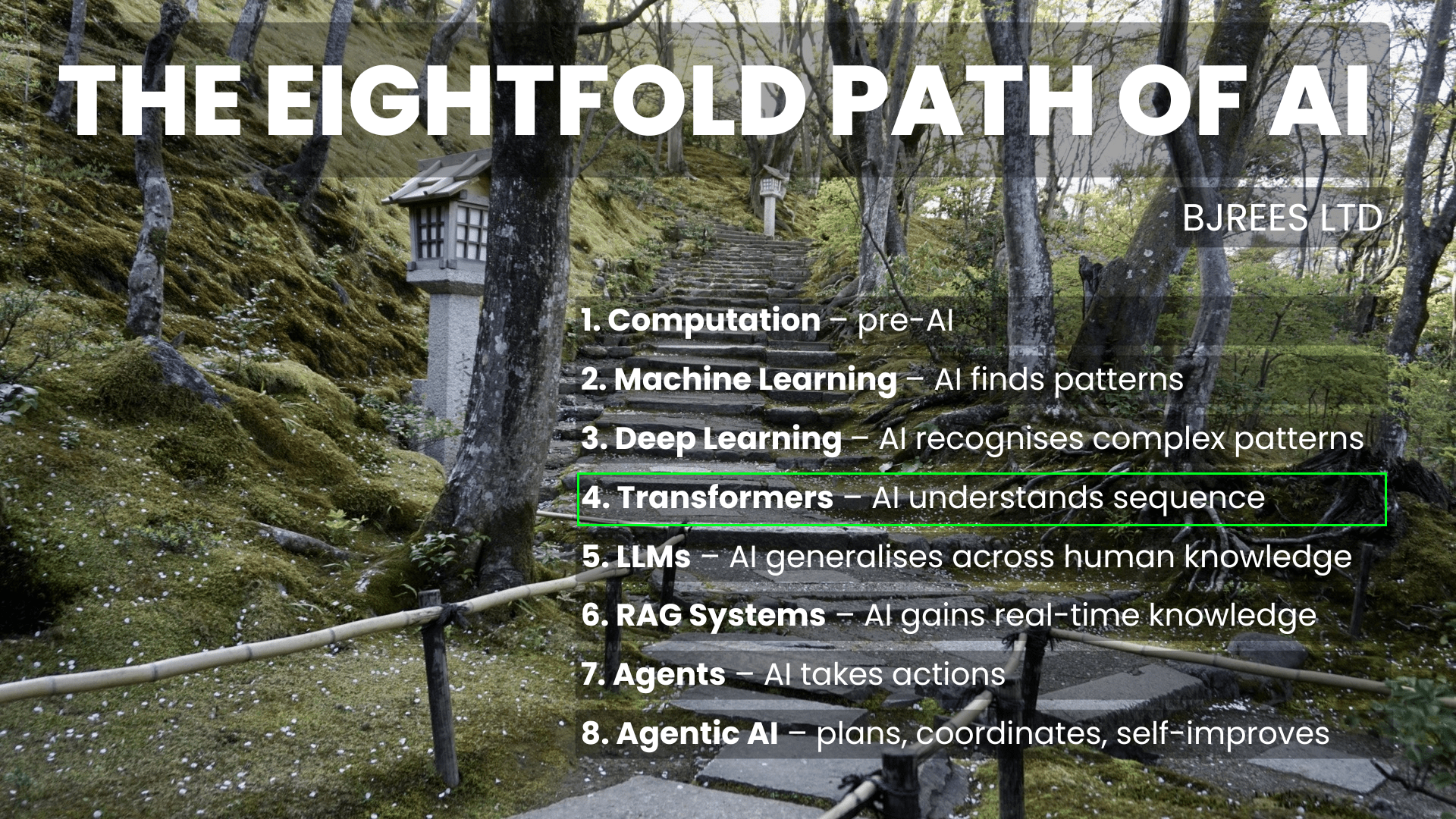

The Eightfold Path of AI

The Transformer and the Architecture of Attention

By the early 2010s, deep learning had demonstrated that learning representations directly from data could outperform rule-based systems and handcrafted features. But despite this progress, the field remained fragmented. Convolutional networks excelled in vision. Recurrent neural networks dominated language. Sequence-to-sequence models could translate text, but only with difficulty. Each architecture solved its own problem class, and none scaled gracefully as tasks became more complex or data grew.

The underlying issue was structural. Deep learning could extract hierarchical patterns, but older architectures struggled to model long-range dependencies or capture rich contextual relationships. They processed information sequentially, layer by layer, token by token. For language especially, this became a bottleneck. Models could recognise local structure but struggled with global coherence. It was increasingly clear that something new was required – a model capable of learning relationships across entire sequences in parallel.

That breakthrough came in 2017 with the Transformer. Its central innovation was simple enough to state: instead of processing sequences step by step, the model learned what to pay attention to. Attention mechanisms allowed the network to weight every position in the input relative to every other position. Context was no longer a side-effect of architecture; it became the architecture. This was the moment when deep learning gained flexibility, scalability, and the capacity to generalise across domains in a way earlier systems could not.

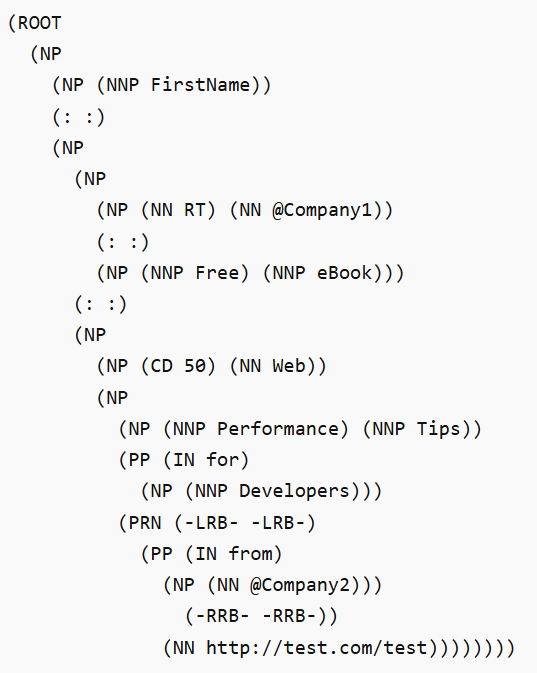

I spent time in 2016 working on the sentiment analysis of Twitter. Maybe I should resurrect that work..

* Manning, Christopher D., Mihai Surdeanu, John Bauer, Jenny Finkel, Steven J. Bethard, and David McClosky. 2014. The Stanford CoreNLP Natural Language Processing Toolkit In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, pp. 55-60. [pdf] [bib]

‡ L. Derczynski, A. Ritter, S. Clarke, and K. Bontcheva. 2013. “Twitter Part-of-Speech Tagging for All: Overcoming Sparse and Noisy Data”. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing, ACL.

From Sequence Models to Attention

Before transformers, sequence modelling suffered from structural constraints:

- RNNs processed tokens sequentially, creating bottlenecks.

- Long-range dependencies degraded due to vanishing gradients.

- Parallelisation was limited, slowing training dramatically.

Attention replaced recurrence with a mechanism that directly measured relationships between elements. Every token could “attend” to every other token in the input. The model learned patterns of influence, creating a map of contextual importance.

This was more than a performance improvement; it reframed how models understood structure. Instead of compressing history into a fixed-size state, transformers allowed context to remain distributed and accessible. Meaning could be captured through patterns of attention rather than through sequential logic.

In technical terms, this enabled three critical behaviours:

- Parallel computation across tokens

- Stable gradients, allowing deeper architectures

- Scalable capacity, making large-scale training feasible

These properties would become essential as datasets expanded through the late 2010s and early 2020s.

The Architecture That Changed Everything

Before stage 4, before proper LLMs became commercially available, there had to be an architecture created – Transformers

The original transformer model – Attention Is All You Need – introduced several ideas that shaped the next decade of AI.

Multi-Head Attention

Instead of learning one pattern of relationships, the model learned several in parallel. Each head captured a different type of structure: syntactic, semantic, positional, or relational.

Positional Encoding

Because transformers abandoned recurrence, they needed a new way to represent order. Positional encodings allowed models to learn sequence structure without sequential operations.

Encoder–Decoder Framework

The transformer separated representation (encoder) from generation or prediction (decoder). This modularity helped later models adapt the structure for language modelling, translation, summarisation, and coding tasks.

The transformer’s modularity and efficiency led to rapid adoption. Within a few years, it became the dominant architecture across NLP, vision, audio, protein folding, and multimodal systems.

Why the Transformer Mattered

The impact of the transformer can be captured through three ideas:

Context Became Computation

Attention mechanisms allowed models to learn relationships between elements directly. This meant complexity could be expressed through relational patterns rather than sequential memory. Models became more globally aware.

Scaling Laws Emerged

Researchers discovered a predictable relationship between model size, data size, and performance. Larger models trained on larger datasets produced reliably better generalisation. This insight underpins every modern foundation model.

Foundation Models Became Possible

Transformers unified representation learning in a way previous architectures could not. They allowed large-scale unsupervised training on vast corpora, creating rich embeddings that transferred across tasks. This made it practical to build general-purpose systems rather than narrow models.

This period marked the transition from specialised neural networks to large-scale pre-trained models that could solve multiple tasks with minimal adaptation.

And Transformers became the foundation of:

This was also a period where I was thinking about a question that has become far more prominent in the last few years – were we in the early days of building something that we should be a little bit more careful of?! What was going to be the impact on our roles? A key question that has been developing over subsequent years.

Transformers in Practice

Across industry, transformers began to appear in:

- translation and summarisation

- search and retrieval

- recommendation systems

- code completion

- anomaly detection

- customer insight modelling

Businesses observed that the same underlying model could be fine-tuned for many tasks, reducing engineering complexity and enabling rapid experimentation. For marketers, this era set the foundations for the generative tools now common in 2025. Modern content engines, semantic search, and conversational assistants all trace their lineage to transformer-based architectures.

In my own work, the conceptual shift was striking. Earlier models felt constrained – narrow systems attached to narrow datasets. Transformers introduced a sense of generality, the idea that a single architecture could absorb and integrate knowledge across domains. This perspective profoundly influenced how I later approached content, experimentation, and AI-driven marketing systems.

The Transition to Foundation Models

Stage Four ends at the moment when transformers became the dominant architecture but before they evolved into the enormous pre-trained models that power today’s generative systems. Transformers provided the machinery, but foundation models provided the scale and ambition.

The next stage explores how these large models emerged, how pretraining reshaped the direction of AI research, and why general-purpose systems became the natural consequence of scaling trends observed during the early transformer era.

Summary

- Transformers replaced sequential processing with attention-based architectures.

- Attention enabled models to capture long-range relationships in parallel.

- Scaling laws emerged, showing that larger models perform reliably better.

- Transformers unified deep learning across domains, enabling transfer learning.

- Stage Five introduces foundation models built on massive-scale pretraining.