-

Why Doing Nothing Inevitably Leads to Failure

Every new idea is a bad idea. Well, not quite, but every time you choose to do something new, there always seems to be 100 reasons why it’s going to fail. Wrong people, not enough people, misunderstanding of the market, can’t extract value from it, too many changes needed, not our core competence, not completely

-

Why Complex Decisions Inevitably Take Weeks

I often find that, when it comes to make certain types of decision in an organisation, this just seems to take weeks. And if you’re unlucky, this can roll in to months. Why? What is it, a lack of decisiveness? An unwillingness to commit to anything? Lack of identification of a “Decision maker”? Just weakness!?

-

How Short Term Data Driven Decisions can be Dangerous in the Long Term

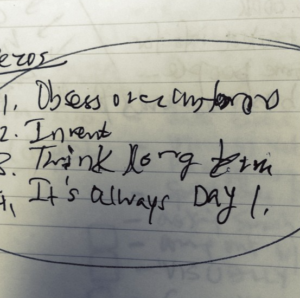

Jeff Bezos’s letters to shareholders are, of course, famous for their insight, not only in to how Amazon functions, but also for their advice on how to run a certain type of business. One of my favourite excerpts, from the 2005 letter is: As our shareholders know, we have made a decision to continuously and significantly

-

Guerilla Marketing for Startups – An Example

We’re on holiday at the moment, in the Netherlands, but just thought I’d write a short post about a great example of guerilla marketing we spotted today, for something we visited whilst in The Hague. There’s a great attraction in a small basement near the centre of The Hague, called Amaze Escape – http://www.amaze-escape.com. Essentially

-

Why Measuring Marketing ROI is Like Trying to Measure Employee ROI – Impossible!

I’m beginning to think I might need to change the tag line for this blog. One of my earliest posts was about how we needed to apply some scientific rigour to the process of marketing attribution and therefore ROI. How can marketers be getting away with such unproven and unprovable techniques, spending all this money

-

Setting Ambitious Marketing Targets is a Waste of Time

We all, periodically set targets for ourselves and/or other marketing folk. How often have we started the year with a plan that goes something like this: Do activities a, b and c, Through activities a, b and c, achieve the following “up-and-to-the-right”* targets: Great, we’re all rich! But what I want to argue is there

-

Process Hawks and Doves

In US politics, and now politics around the world the terms “hawk” and “dove” (really “war hawk” and “war dove”) are used to identify politicians who have leanings in a particular direction – either towards controversial wars or against. The arguments always play out on both sides, hopefully tending towards a solid, well-argued solution for

-

Getting Stuff Done as a Product Marketing Manager

I hardly know a Product Marketing Manager who isn’t overwhelmed by his or her workload. As I’ve written previously, this is at least in part because of the vast number of activities that PMMs “should” be doing – how can you not being doing your job properly if you don’t, at least, have a full

-

The Need to Constantly Change in Marketing

There’s a quote that I really like from one of Christopher Isherwood’s early novels, The Memorial: “Men always seem to me so restless and discontented in comparison to women. They’ll do anything to make a change, even when it leaves them worse off. […] Whereas […] we women, we only want peace.” Removing the sexism

-

Increase Your Net Promoter Score to Decrease Marketing Spend

Marketing budgets are always on the squeeze. Or may be less that money is tight and more that the expectations on Return on Marketing Investment (ROMI) are raised. “I don’t mind spend £50k on this campaign, but I want to know what return I got, or you won’t have £50k to splurge next year”. The

-

The End of the Marketing Plan

I’ve read a couple of books in the last year both with something to say on the subject of marketing plans. Well, I’ve read one and given up on the other. The one I finished was: Lean Enterprise by Jez Humble, Barry O’Reilly and Joanne Molesky And the one I barely got started on was:

-

Keeping an Eye on The Competition

Many, many years ago I studied psychology and one of the most interesting courses I did was on development psychology – how we go from babies to infants to toddlers to children to teenagers to adults. The most fascinating lecture series was on Theory of Mind – the notion that, as we grow up we

-

Xbox One vs. PS4 – How Marketing can Drive Development

Hard to miss it, but two next-gen gaming consoles were launched just before Christmas – Microsoft’s Xbox One, and the Playstation 4. Normally this sort of thing would pass me by (I’m not a big video game fan – they just seem like complete time vampires), but something I noticed was how interesting the two

-

Dissecting Thought-Leadership

To start, I don’t really like the term “Thought-Leadership”. Like many things in marketing, it’s a bit too “marketing-ey”. It also has echoes of NLP, something I’m not a big fan of, to say the very least. But, I guess it’s pretty descriptive for what it means – I’d define it as something along the

-

My 10 Biggest Marketing Screw-ups of 2013

It’s nearing Christmas, time for “Top 10…” and “Round up of 2013″ style posts, so here’s mine. One of my failings is that I’m a terrible self-critic, so I thought I’d write a piece on “My 10 biggest marketing screw-ups this year”. I don’t think I’ll get fired because luckily I work at a place

-

Market Sizing – Old vs. New Markets

I was attempting some market sizing activity this week. It’s something I haven’t done for a few months and quite frankly I’d forgotten how hard it was. I start from a premise that the future is completely unpredictable. Really, aren’t we kidding ourselves when we think we can predict how many people will buy our

-

Working on the Coalface

Everyone who works in marketing and product management should be spending as much time as they possibly can with customers. Period. This is, of course, a bit of a bland and obvious statement (like all those marketing books that promise so much and deliver so little!) – we know this, we don’t have to be

-

My Product is Great. Why Do I Need a Marketing Department?

Well, I still hear this question and there is some logic behind it. I’ve created a product of beauty and wonder, why do I need to invoke the dark arts of marketing to get it out there? Won’t its greatness shine through and act as a beacon to all those lovely customers with their dollars

-

Waiting for Google

This isn’t going to be a very exciting post unfortunately, though it was supposed to be. I visited the UK Google offices this week to have a chat about the future of Google Analytics, well Google Universal really. I was hoping for some help, some tricks and tips, perhaps a few sneak peeks at a roadmap

-

What I Should Be Doing as a Marketer. But Won’t Be

“Should” is a complicated – and dangerous – word in marketing. How many times have you read blogs and articles proclaiming that you “Should be doing more mobile marketing”, that you “Should have full content strategy”, that you “Should be creating personae for all of you target segments”, “Should be doing more on Twitter”? And

-

Measuring Offline to Online Marketing Attribution

This post is about one of the many issues facing anyone trying to do marketing attribution – how do you measure the impact of offline activity on online success? If you’re selling online, but you’re carrying out offline activity (TV ads, magazines, direct mail, events, arguably word-of-mouth) then you don’t get this sort of insight

-

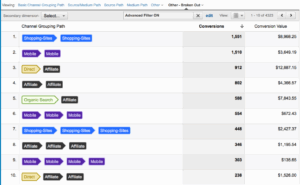

When Marketing Isn’t Really Marketing – Google Analytics Multi-Channel Funnels

I was excited this week about the prospect of finally having the time to play with Google Analytics’ advanced Multi-channel Funnel (MCF) functionality. As announced at their summit last year, they’ve extended their advanced attribution modelling to all GA users and this provides the opportunity to (finally!) try and attribute some measure of value to

-

SaaS Product Management, Lovefilm and Getting Stale

Lovefilm have just revamped the app that is used by devices such as Blu-ray players and the PS3 and it is, in my opinion, a great improvement. There are a large number of changes but I think also, and I’m speculating massively here, that the improvements were heavily shaped by some great data driven product

-

How To Measure Campaign Success

Quite a simple post this time round. Essentially how I measure the success of a given campaign or piece of marketing work. NB: This isn’t the Holy Grail of properly attributed marketing ROI – when I’ve worked that, I’ll post it up, if I haven’t retired first – but instead a framework for how to

-

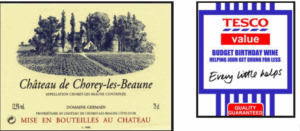

Value and Predictable Revenue Improvements

I really like this very simple post about how to buy wine, when you don’t really know much about it (which is definitely me). Basically, select a price (say, £7.95), then select a wine at that price. That’s kind of it. And what Evan Davis is saying is “Statistically, give or take anomalies, most wines

-

Competition, Disruptive Innovation and Total Recall

A key part of any product marketing role is analysing the competition for your product. Put simply, when your potential customers are looking to solve a particular problem or take advantage of an opportunity, what are the options that they see, one of which (hopefully!) is you? Sometimes this job is easy when you have

-

Why Product Managers Often Aren’t Great at Marketing

Back when I was a developer, many years ago, I worked with a superb sales person – an ex-McKinsey sales person – who had been tasked with explaining to all us techies “What Sales Did”. Of course we already knew the answer – “Nothing, except get paid more than us, drive nicer cars, get more

-

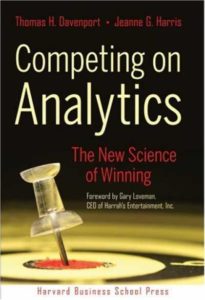

Five Tips for Implementing Marketing Analytics

The book Competing on Analytics by Thomas Davenport and Jeanne Harris is a short but very interesting read about the need for organisations to significantly improve their analytical capabilities if they want to compete in the modern marketplace. The argument, quoting directly from the author is that: In today’s global and highly interconnected business environment,

-

Book Review: Positioning by Al Ries and Jack Trout

Another book review this week, this time Positioning by Al Ries and Jack Trout. Obviously this is a book that had been around a long time. And there are endless reviews, over the years with different opinions. However, what’s interesting from skimming through the Amazon reviews, is that there’s a real mix between people who

-

Is it the Content or the Author that Matters for a Blog?

If, like me, you subscribe to a lot of marketing RSS feeds, then you can’t have failed to notice the almost overwhelming proportion of posts about content marketing/SEO and how choosing appropriate and useful content for, say, your blog is a killer way of drawing in early stage leads. This SEOMoz post is a good

-

New Year, New Markets, New Products

Many of us will have come back after the Christmas break trying to think of new activities, new ideas and new opportunities for 2013. One of these is – is there some new product, proposition or market we could address, obviously with a view to expanding the addressable market, or creating new revenue streams? Easy,

-

Product Management and iTunes 11

Just to start – this isn’t another post written just to whinge about iTunes. It’s a post written to whinge about iTunes and its relevance to product management. Is the following situation familiar? Product manager or marketer wants to add new features, use-cases and options to their product, based on customer feedback, that they think

-

Favourite marketing posts of 2012

This post is now 11 years old so a lot of the links no longer work! This is my last post of 2012 before breaking up for Christmas and I thought I’d finish with one of those lazy “Everyone’s out for Christmas, let’s just re-use some old material” posts, summarising my favourite articles that I’ve

-

Lean Personas – How to Make Personas More Useful

First of all, I prefer the term “Personas” to “Personae”. Doesn’t “Personae” just seem pretentious, n’est-ce que pas? Anyway, the point is, I’ve always struggled, over the years, to find personas a useful tool in marketing. I’m specifically talking about marketing here, rather than user-centred design – I know these are two sides of the same coin,

-

Product Marketing and Product Management Roles

I wrote a brief post, about the different roles in the area of product management and product marketing, so it was interesting to read what Saeed Khan had to say on the subject in the following two posts (the first one in particular): http://labs.openviewpartners.com/role-of-product-marketing-in-your-startup-part-1/http://labs.openviewpartners.com/role-of-product-marketing-in-your-startup-part-ii/ These posts give really great insight in to what the different

-

Are you doing marketing or Marketing?

Very interesting post here from the start of this year, from Joshua Duncan: http://www.arandomjog.com/2012/01/the-end-of-product-marketing/ In it, Joshua describes how the role of Product Marketing Manager (PMM) is, essentially, moribund – not because the work done by these people isn’t required, but because these activities are rapidly being taken up by other individuals (Product Managers, MarComms

-

Marketing and Data Testing

Anyone who’s worked in a digital marketing environment will probably recognise one of the following two scenarios – 1) You’re merrily working through your day when you check up on a KPI graph that normally bobs along nicely only to see some unpleasant looking change (generally a “drop” of some sort). Panic. 2) You’re merrily