-

Strategic marketing – knowing where to place your bets

Strategy is about making choices. If you’re not stopping some activities or choosing to not do something then you’re not being strategic. Easy to say, less easy to implement, particularly when the organisation wants “More leads, more leads, more leads!”. How do you say “I want to do less”? Almost everything in the world of

-

Scaling up marketing

Scaling up marketing

-

B2B marketing help

One thing I learned very early on in my career – you can’t do a marketing job without almost constant interaction with the rest of the business. Whether that’s the sales team, the product team, HR or anyone else, you need constant input and feedback from both inside and outside the building. One very specific

-

Creating a marketing strategy plan

What should be in the plan? When I moved into the CMO role I realised a number of ways in which the position was different to what I had done previously. A lot of these differences are to do with being in a C-level role, but I’ll focus here on the CMO position and the

-

How to add ChatGPT to your own website

There are many stages of exploring ChatGPT: I’ll talk about the first four points here and then, in the next article, the last point. This is a considerably bigger task, so needs a post of its own. The end goal is to allow customers and potential customers to come to your site and ask questions

-

Trying out ChatGPT

Of course, really, we all want to build Skynet. However, until Judgement Day comes, we’ll have to make do with ChatGPT. ChatGPT is obviously a Big Deal right now for marketers, so I wanted to find out for myself. Firstly, as a general point I do think it’s important to try technology out yourself before

-

The Marketing Flywheel

New Year, new marketing plans. Hopefully by now you’ve kicked off various activities and you’re waiting to see how those early campaigns are working out. The other thing I see in marketing departments at this time though is burnout. Everyone is trying to do everything either because there’s no real strategy there (“let’s throw everything

-

The marketing flywheel – an alternative to the marketing funnel

A lot has already been written about how the old marketing funnel model is no longer as relevant in modern B2B organisations as it used to be, and how a flywheel model is more appropriate for how customers really buy (as an old colleague said to me “The person who invented the marketing funnel should

-

How to make decisions

There’s a myth that as you get more senior, you get to make more autonomous decisions about what happens in your business – what strategies to pursue, tools to buy, markets to go after and so on. “I’m the Head of Marketing, so surely I decide all the marketing stuff!?” In fact it’s the opposite

-

Beware roles that advertise long hours

A friend is looking for a new role at the moment. He’s lucky enough to be able to pick and choose what he goes for, so I asked “What really attracts you to a job? What puts you off?”. It’s always interesting to know what people are looking for, how to genuinely attract great candidates

-

Why ROI calculators aren’t enough

ROI calculators are a pretty common tool amongst B2B marketers. On the face of it, the logic is simple – show a calculation of how the time saved from subscribing to your product equates to money and how that money is less than the annual subscription cost charged. Then surely the sale should be in

-

Scaling from SMBs to the Enterprise – a 10-Point Plan

I’ve had this conversation about 6 times in the last year – how can you scale from selling to small businesses (SMBs), up to Enterprise organisations? What are the marketing challenges? What’s necessary, what’s nice-to-have, and what’s a red herring? This is something we’ve done incredibly well at Redgate over the last five years (from

-

How We Grew Marketing Sourced Pipeline by 20% in One Quarter

We’re about to go into our quarterly review period at Redgate. We don’t just run QBRs, we also run reviews across all parts of the business. These are a chance to examine the last three months – what worked? What’s going well? What’s not going well and needs fixing? All part of a strong agile

-

How Collaboration Can Grow Revenue

Why do Marketing and Sales departments need to collaborate? Sure, it’s nice, but beyond people getting on better together, how can it really impact the numbers, the outcomes for the business? We’ve just spent a month at Redgate improving the collaboration between the two departments and we can see the direct and measurable impact on

-

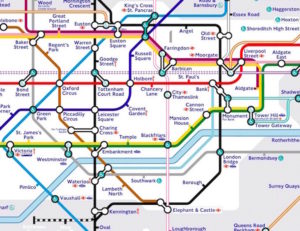

Getting from Green Park to King’s Cross

Anyone who has used the London tube system much, will know that there are two routes from Green Park to King’s Cross – the Victoria Line and the Piccadilly Line. The Victoria Line is the “Right” way to get from Green Park to KX – it’s quicker with fewer stops, why wouldn’t you take this

-

Working from Home

Lots of people have written about the “New world of remote working” (so much so, that that phrase has become a cliche in the space of six months). But I think it’s still an interesting topic, because I have a hunch the changes we’ve seen in 2020 will become permanent, even as we start to

-

How to Present to an Exec or Board

For better or worse I find a lot of my tips and tricks for working in a software company from fiction books and films. I learnt most of what I know about how to present to senior folk (an Exec team or a Board even) from a two-minute scene in David Mamet’s film “The Spanish

-

Join a Scaleup to Scale Your Career

It’s hard getting ahead in Marketing. It’s a discipline changing every year (certainly true of 2020), it covers an enormous breadth of disciplines which need a great variety of skills and it’s notoriously difficult to prove the impact of your work. So what can you do to give yourself the best chance of success? Of

-

Under-promise, Over-deliver for product-led growth

There’s a lot written about the advantages of product-led growth (PLG), how it keeps marketing and sales costs down, how customers prefer it and so on. All good, but I struggled to find much on the actual strategies to use – how do you do it? There are obvious things like having a product with amazing product-market

-

External Marketing during COVID-19

Everyone’s got marketing advice about what to do in the current crisis, haven’t they? As though it’s easy and obvious what you should be doing in this “first-in-a-lifetime” situation we find ourselves in?! I don’t think it’s easy and obvious at all. But if you work in marketing, now is the time to earn your

-

There are two times when you don’t need to worry about Customer Success. And neither apply to you

Another thought exercise. I was trying to think of scenarios where Customer Success – i.e. genuinely worrying about whether your customers were using and getting value from your offering – wasn’t going to be a priority for a business in 2019. I could only think of two. But I think even these are slightly fatuous, I’d be

-

Focus on Marketing Effectiveness to Scale Up

Here’s a very non-theoretical problem – you’ve got two ways of spending some digital marketing budget, either a) LinkedIn advertising, or b) Facebook advertising. The former works pretty well, you manage to calculate a return of $1.50 for every dollar you spend. The Facebook adverts are more effective though – a return of $1.80 for

-

Finding Balance in Marketing Strategy

It’s that time of year again (for us anyway) – putting together the detailed marketing strategy and plan for 2021. And yet again it’s hard going. I’m not complaining – if it’s not difficult, then you’re not doing it right. Our job as marketing leaders is to work through the almost-overwhelming volume of data and

-

Why HR is the Most Important Department in your Business

Surely not!? Surely it’s the Marketing department (I am a marketer after all)? Or maybe Sales, maybe Engineering, maybe Customer Support. But no, I want to argue that getting HR right is one of the step changes you can make to a business, with far broader impact than any of the areas listed above. There

-

Five Myths About The Marketing Revenue Engine

I love the book Rise of the Revenue Marketer. In it Debbie Qaqish describes the need for a change program to move your marketing department from being a cost centre (“We’re not sure what marketing do, but we need them to do the brochures”), to a revenue centre (“They’re responsible for generating a significant proportion of our company’s

-

Review: “Subscribed” by Tien Tzuo

The Subscription Economy is the idea that more and more customers (and therefore vendors) are moving over to being subscribers of services rather than purchasers of products. An obvious example is Spotify – the money spent by consumers on streaming services now significantly outweighs revenue from physical CDs or even digital downloads: In 2019, more money is

-

Building a MarTech Stack at a Small Organisation

I recently spoke at the B2B Ignite conference in London on “Building a MarTech Stack at a Small Organisation: A Real World Example of What’s Worked and What Hasn’t”. Here are my slides from that talk. Rules of Thumb It’s a lot of pictures, so might be hard to understand without the actual talk! Any

-

Measuring Outbound vs. “Always-on” Marketing Performance

Whenever I meet customers I always slip in a marketing question or two along the lines of “Where did you hear about us? What brought you in to Redgate?”. One of the answers from a couple of months back was: Well a year ago, I got a new boss and she told me that I had

-

Brand Amplifiers

I’m writing this on my way to the Sirius Decision Summit in Vegas (sitting in Terminal 3). I’m hoping to get a lot out of the conference (though I’m currently in option paralysis mode – too many sessions to choose from). But this post is about a very small part of that conference – though

-

Your Customers Pay Your Salary (not your Employer)

“Don’t find customers for your products, find products for your customers” – Seth Godin The simplest ideas are the best. But they can also seem the most banal. Hidden in the Seth Godin quote above is, I believe, one of the key differences between a mature and immature organisation. Between a company that is ready

-

To learn about the “Buyer Process” try buying something

I guess this is more a post about sales rather than marketing per se, but still – understanding buyer journeys and how you can help at different stages is an important part of the marketing role, particularly when the sales cycle is complex. I’ve read quite a lot about marketing funnels – how customers at

-

You’re applying Marketing Theory, But You Don’t Even Know It

I love this article from Helen Edwards – about the need to understand marketing theory but then the need to apply it to the real world. Theory without execution is just an indulgence, a wholly academic pursuit. But if you’re executing well against a poor strategy, you’re just peddling fast in the wrong direction. She provides some

-

Sentiment Analysis of Twitter – Part 2 (or, Why Does Everyone Hate Airlines!?)

It took quite a while to write part 2 of this post, for reasons I’ll mention below. But like all good investigations, I’ve ended up somewhere different from where I thought I’d be – after spending weeks looking at the Twitter feeds for different companies in different industries, it seems that the way Twitter is

-

There are Three Types of Marketing – Inbound, Outbound and… Plain Rude

Reading one of the many number of content marketing pieces from HubSpot, I noticed the following from a basic piece on What is Digital Marketing?, after paragraphs about the virtues of Inbound marketing techniques: Digital outbound tactics aim to put a marketing message directly in front of as many people as possible in the online

-

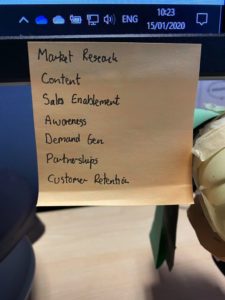

Your Primary Job as a Marketing Leader is to Prioritise

I’ve just finished the excellent Complete Guide to B2B Marketing by Kim Ann King. It’s very “List-ey” – it’s full of To Do lists (“Want to figure out your budgets for media spend? Here’s a 7-point list of how to do it”), which I really like. Many marketing books are rather waffly and vague, so a

-

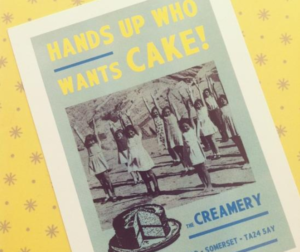

Anatomy of a Great Ad

It’s easy to forget, amongst the talk of marketing automation, social media strategy, customer experience, lead nurturing and so on, that you still need well written, well targeted and well designed ads to reach new customers. I spotted a great example this week, and just wanted to run through what I thought was great about

-

Sentiment Analysis of Twitter for You and Your Competitors – Part 1

This post is split in two, primarily because I hit a roadblock half-way through the work – and I wanted to get the first part out. Second part to follow once I’ve fixed the difficult problems! A lot of people follow the Twitter feeds for competitors or, of course, themselves. But, one of the things

-

Write Content That People Actually Want to Read

This feels like a pointless blog post – the think I’m going to say seems so obvious, I shouldn’t need to say it. Still, I see examples where this doesn’t happen, so perhaps it’s worth re-iterating the point. Here’s the incredible insight – if you want people to read content that you write, then it

-

Measuring Customer Experience

Customer Experience (CX) – it’s a popular topic right now, analogous to the importance of User Experience (UX) in the world of product development. And something which I strongly believe is important for a marketing team to get right. So, we all know that getting your Customer Experience great and consistent is important for all of

-

If a Brewery Can Innovate, So Can You

This weekend we went to Southwold and Aldeburgh – two of my favourite places in the UK, for various reasons. One of these reasons is the Adnams Brewery, based in Southwold. It’s been going for over a century and has always produced wonderful beer (as well as other drinks). But a few years ago I

-

Your People Are Your Customer Experience

We went to Milton Keynes today (school holidays – where else would you want to go?) and there were two examples of what I’d call, using marketing jargon, “A great customer experience” for the children. Listening to them talk about it afterwards, it wasn’t just something to do with the actual places we went to,

-

People. Customers. Action.

I was mugging up again last week on the McKinsey 7-S Model, now pretty old, but I still think a great framework for looking at organisational effectiveness. All very interesting, but then I found the post that Tom Peters wrote about the book decades later and found a quote that I particularly liked: “You could boil

-

Human Beings are Holding Back Machine Learning

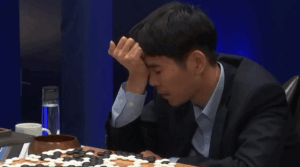

Machine Learning (ML) and AI are big topics right now. Poor Lee Se-dol has just been beaten by AlphaGo – a machine put together by Google/DeepMind and there are numerous other examples in the news.So everyone is interested, and everyone wants to do more of it. Whether you work in marketing or any other discipline, there’s

-

Why You Can’t Pivot as Quickly as You’d Like

There’s a great scene, towards the end of the film American Sniper, where Bradley Cooper’s character has to take a shot from over a mile away from his target. But the point is, there’s a long time between the point he takes his shot, and when he finds out if he has hit or not.

-

Better to be in the Arena Fighting…

A place I used to work, perhaps 10-12 years ago, had (what I think, now) was a strange custom. Every Monday morning the whole company would get together to go through everything. There were around 70 of us, at the peak, and we would all stand around from about one-and-a-half hours going through sales, marketing, development, ops,